PART II

Who Grows

Your Food?

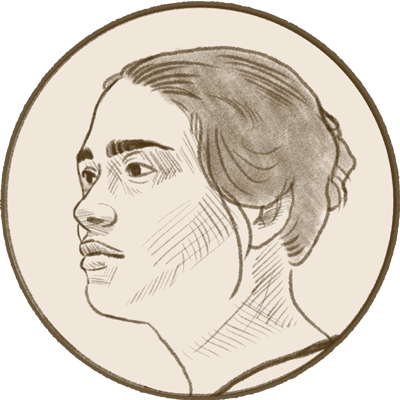

By: Leonina Arismendi Zarkovic

PART 2 of 6

Who Grows

Your Food?

By: Leonina Arismendi Zarkovic

Part two of a series focusing on the lives, struggles and joys of undocumented farm workers in the American agricultural industry. Names have been changed and locations are proximal, not exact, in order to protect identities. These are true undocumented farmworker stories.

Content Warning: this story contains mention of sexual harassment, inhumane working conditions and exploitation.

In The Hot House

The state of Virginia’s largest private industry is agriculture, and it ranks third in the nation for tomato production(1). Over its 8 million acres of agricultural land, there are nearly 6000 immigrant farm workers that come to Virginia each year to harvest crops(2).

These farmworkers, in Virginia and across the US, are responsible for a large amount of the produce we buy at supermarkets and eat today. Regardless of whether produce is organic, non-GMO, or conventional, the living conditions, treatment, and labor of farm workers are far from humane, and surely doesn’t fit under the regenerative agriculture principle of “human and animal welfare”.

A regenerative system is one that supports life and biodiversity. It includes healthy and equitable relationships with all, including farmers, farm workers, and all the hands within and throughout the supply chain that touch the produce. To envision a regenerative food system, we can’t move forward unless we acknowledge, and work to diligently transform, the current food system that is extractive and exploitive for millions of human beings right here in the United States. Immigrant farm workers often live in labor camps on their employer’s property with minimal amenities, dilapidated rooms, and improper toilet and bathing facilities.

When talking about undocumented communities, it is important to note that most folks go underreported and underrepresented for obvious reasons. Most of whom work in the construction, agricultural, food service and hospitality sectors and are paid far below minimum wage with no benefits, yet still pay taxes and contribute to the wealth of a state.

In Virginia, undocumented people fly under the radar, praying that things will get better. Nora is one of these folks, and this is her story.

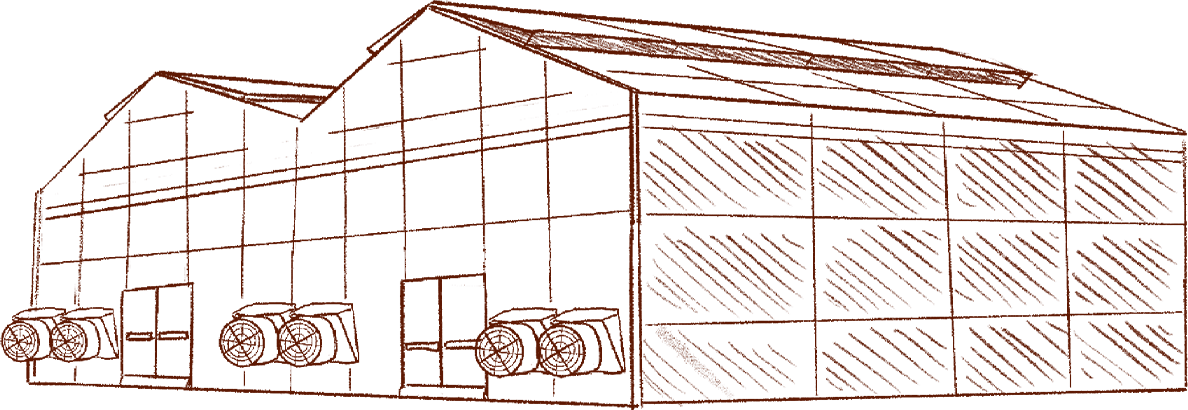

A hot house is essentially a heated greenhouse. Hot houses allow farmers to grow crops throughout the year, even in the cold of winter. Nora’s experience at the hot house, where she grew tomatoes and seed trays for nurseries was far from what she expected.

Nora:

“I thought, what better place to work than to grow plants? I always worked the earth and love to do so, a greenhouse really sounded like the most perfect job I could have in my position,”

Me:

“when you say your position, that means… “

Nora:

“…you know freshly arrived to the country, without papers. When you do not have papers, it is easy to accept a lot of bad things at work. Like I told you, when my manager at the restaurant wanted me to sleep with him, I was done.”

I feel her words, having experienced different manners of exploitation and horrors in the twenty years I have lived here. When we come here, eager to find a better life, most of us do not have a clue that the immigration system is not just flawed but designed to keep a majority of people in a state of marginalization due to status. Being undocumented is a ripe condition to be taken advantage of because it’s such a vulnerable position. The current immigration system is just a caste system that determines who is an ex-pat, an immigrant worth keeping (a model minority worthy of being granted documentation) and who will be tied to a new system of modern day slavery.

Nora came here seeking opportunity and a future for herself. She had experienced growing food and working the land in her own country since she was a child, but more than that, I could tell she had a green thumb, that magical j´ne se quois that accompanies some farmers auras. Sitting under trained indoor vines, she was perfectly at home. Growing food was not something she learned, but a common skill she acquired as part of her culture and community growing up.

She can become Mother Earth in the flesh at any given moment, to both her children and the plants she tends.

On a cold February day, we met for cafecito and a warm embrace wrapped in banana leaves, known to us mere mortals as tamales, the sacred food of the Gods. She was excited to show me her garden beds, already prepared for the spring, seedling cups labeled carefully in her kitchen, and every plant that occupied her immaculate living room by name.

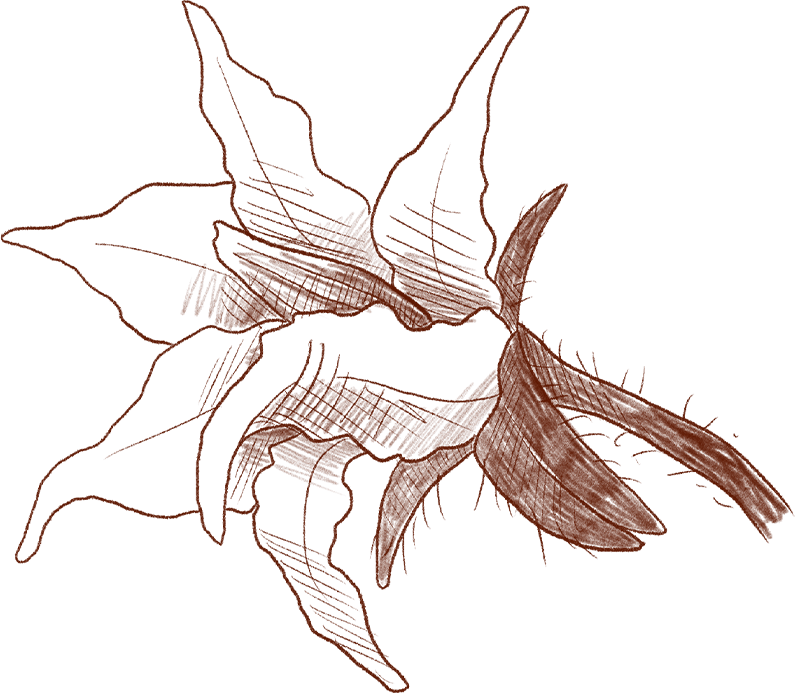

Growing seedlings is still one of her favorite things to do. She loved that part of her work. She also liked the bonus of getting free tomatoes from work to give to her family and apartment community.

“I always thought of where the little plant might go. Who might pick it up, wishing that a good person would take care of it and not neglect it, and then imagining them enjoying the fruits of their labor. I would get excited when I would go to the garden center and see seedling trays there, I had no way of knowing if I even made that tray but I still felt proud! I did not care about the tomatoes we grew there very much though, they were thin skinned, frail and the way we grew them felt unnatural. One thing I did love was to pick a tomato off the vine and taste it right away, especially when the tomato is warm from the sun… I still took some home and made good sauces anyway,” she laughed.

Nora’s knowledge of agriculture stems from a lineage of land stewards in Honduras. She immediately recognized the unnatural ways the industrial farming systems grew “food”, yet how could she possibly voice her opinion in a system that barely recognized her as a human being? Nora worked alongside a cohort of fellow immigrants with similar backgrounds, who all shared similar experiences.

She describes her co-growers as amazing people who are hard working and deserve many blessings.

Management was a different story…

Nora:

“They were Latinos too, usually stuck up because they had papers. They made a little bit more money, they spoke English, had cars and licenses so they treated us like we were inferior. The Americans, management or not, usually did not even speak to us, most of the time they confused my name* (Nora’s real name is a variation of a very popular LatAm name.) ”

On her second summer working at the hothouse, the company made a decision to close its doors in the hottest months of the year citing employee safety. Nora tells me that no one was given any sort of proper notice nor compensation for the time loss and she had to really scrape by those months without work.

Nora:

“They said it was for our safety but the reality is that the hothouse was hellish at any time of the year. They did not want a lawsuit or for anyone to investigate–people passed out all the time. Dehydration, lack of sleep, overwork. Heatstroke. Headaches. Bone Problems.

I know a girl that had a miscarriage, she swore it was because the heatstoke she had, she was seizing on the floor. She went to the hospital and was given fluids and sent home. As a mother I trust what she says happened. She quit after that. You were advised to wear long sleeves and closed shoes since we worked with chemicals, and a mask. I have been used to wearing masks for years now! I always had to wear one at work, not just because of the chemicals and the stuff in the air, but because if someone went to work sick, the flu would spread fast in the heat.”

Nora:

“Most of the estimated 1.4 million farmworkers in the United States work in crop harvest, usually during the hottest months of the year. The effects of the heat are often exacerbated by humidity; evaporative cooling is decreased and thermal load is increased. This study suggests that farmworkers continue to experience excessive heat and humidity even after leaving the fields. Farmworkers, particularly migrants, have little control over their housing. As it is frequently grower-provided; in other cases farmworkers must rent from a limited supply of low-quality rural housing stock.”(1) Whether inside or out, heatstroke can have lasting effects on people’s bodies.(3)

Nora:

“I love where I work now, it is like heaven to work around beautiful flowers daily. The bosses don’t know which of us might be undocumented, but they care. They even talked to a Senator about how important it is for the government to pass laws that protect us and give us a fair chance to become citizens. They believe in God in a very real way. Did you know the Bible says that you should treat the immigrants in your land well and let them harvest from your crop?”

Me:

“Leviticus 23:22, I am familiar, do you believe this could come to pass? In the USA? A place where people are welcomed and taken care of as we take care of the food system?”

Nora:

“Primero Dios”

Both:

“Amen.”

Driving back to DC from Fredericksburg is always a cathartic experience, I can feel my anxiety lower as we move North and you see less confederate flags. Fields of freshly felled forests stretched out naked, harkening new suburban developments on the horizon.

In a country where there are 33 empty homes per houseless persons(5) and 10.5% (13.8 million) of U.S. households were food insecure this past year(6),

I know a story like Nora’s, like mine, is to some, a shining example of the American Dream story. To others, it is an exception to our expectations – the few that made it in America – and to others, a capitalist nightmare rebranded as positive – the mythos that as an undocumented person, if you hang in there and do the hardest work, you too will achieve your dreams!

Nora has always yearned for family, safety, and green spaces. What writing this series has been for me, has been like seeing her children grow up to have more opportunities than herself. Nora deserves the life she loves and in that space of security, she is able to pour gorgeous, joyous energy into her work.

I like to imagine that magic makes her flowers the most beautiful in the greenhouse. I want to see a beautiful happy ending to all the stories I will gather across the USA this summer. I want to see the old world, the one of my Ancestors, being attuned to Mother Earth yielding the Collective, a food system that abundantly gives medicine, housing, art, knowledge, and Life to all. I believe that understanding the current food systems, how affected people, land and animals are by it, and hearing these stories first hand can radically change how we engage with the food we eat and people who grow it on a personal level, and on a macro-level.

We can, and must, demand more.

SOURCES

Source 1: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3723406/

Source 2: https://www.justice4all.org/current-initiatives/farmworkers-current-initiative/

Source 3: https://www.magidglove.com/safety-matters/safety-training/heat-stroke-facts

Source Source 4: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/443686/

Source 5: https://www.self.inc/info/empty-homes/

Source 6: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/

This piece was written by Leonina Arismendi Zarkoviç, a member of our Circle of Creatives. Leonina is an Uruguayan born Queer artist, translator and human rights advocate. They are recognized as a top-writer in Intersectional Feminism on Medium where they are known for their distinctive writing voice. As Reverend Leo they co-lead Iglesia del Pueblo, an online interfaith gathering space for Latinx movement leaders within the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. Their work focuses on liberation theology, decolonization, womanism, food justice and popular education.

Their background is in urban farming, Ancestral growing and living practices, cooking, art and curation and have formerly owned an art gallery in Virginia.

Leonina’s work exists at the intersection of food justice, art, activism, faith and education. They are known for being very blunt, mostly driven by the urgent nature of the causes they advocate for.

Part I: History of Farm Work as Immigrant Labor

Part one of a series providing both historical and modern framework of what ‘farm labor’ really is in America to help us properly begin telling the stories of Who these Farmworkers Are… Because they are so much more than just ‘those who grow our food’ and they are worth much more than what they bring to the economy and the services that they are capable of providing for us.