3 Major Factors Affecting Access To Nutrient Dense Foods:

Where have all the nutrients gone?

But today, it’s becoming harder to have that experience as the shelves in most grocery stores and supply chains are flooded with perfectly stacked, impeccably round, conventionally grown tomatoes (did you know China is the largest grower of tomatoes?!). Looks can be deceiving. While immaculate in appearance, the flavor and vital nutrients that sustain our health are a fraction of what they should be in most of today’s produce. A tomato grown today has almost no lycopene (plant nutrient with antioxidant properties that give the red color) left in it, compared to one grown in the 1950s. Compared to 50-70 years ago, the food we consume today has significantly less vital nutrients.

NUTRIENT DENSITY OVERVIEW

01

SOIL DEPLETION, FARMING PRACTICES + HIGH YIELDS

After World War II, the United States turned its excess petroleum into chemical fertilizers. Many farmers were convinced that these chemical fertilizers would save time, increase yields, and create healthier, greener plants. Yes, fertilizers contribute to quicker and bigger yields, so it’s easy for farmers to create a dependent relationship with them. When excess amounts of fertilizer are applied, the debate continues on what is compromised in regards to the health and nutrients of the plants and soil. Dr. Zach Bush states, “The plants were greener, but they weren’t healthier—they were now weak and lacking major nutrients. For the first time in history, farmers ignored the generational and indigenous wisdom of good crop practices. They stopped letting their soil rest, they stopped rotating their crops.”

A combination of over-cultivation, overgrazing, excess tillage, and over use of NPK (nitrate, phosphate and potassium) fertilizers are some of the few common practices that are affecting the nutrients in the soil (note that even USDA Organic farmers can till and use organic chemical inputs). Source These practices destroy some of the beneficial microorganisms, symbiotic bacteria and fungi that supply nutrients to crops. If microorganisms are not present, the crop cannot realize it’s fullest nutritional potential. Additionally, critical enzyme systems within the plant roots that help mineral absorption become inactive with an excess of pesticides like organochlorine (OC) and organophosphorus (OP) Source With these farming practices, the land is treated like a factory focused on yields and output, rather than nutritional quality and flavor. High-yield crops burden the nutritional capacity of our soils, affecting their alkalinity or acidity. Source With an imbalanced soil-base, it’s as if the plants are on life support. According to Rodale Institute, there is roughly 60 years of topsoil left if we continue to use conventional practices.

Activist Winona LaDuke argues that the industrialized food system sacrifices nutritional value for efficiency, selecting for crops that produce high yields and resist diseases. The rising intensity of pressure to maintain high yields inhibits farmers from having the time, space and financial resources to try transitioning to regenerative practices – for the farmer, it’s a big risk. However, regenerative agriculture has the potential to offer a solution by incentivizing farmers with higher profit margins based on the nutrient density of their produce over yields. The ideal situation is for farmers to get a fair wage, while also making it affordable to everyone. With less costs for inputs, I believe there is a way nutrient dense, regeneratively grown produce can and should be more economically viable than conventionally grown food.

02

ACCESS AND APARTHEIDS

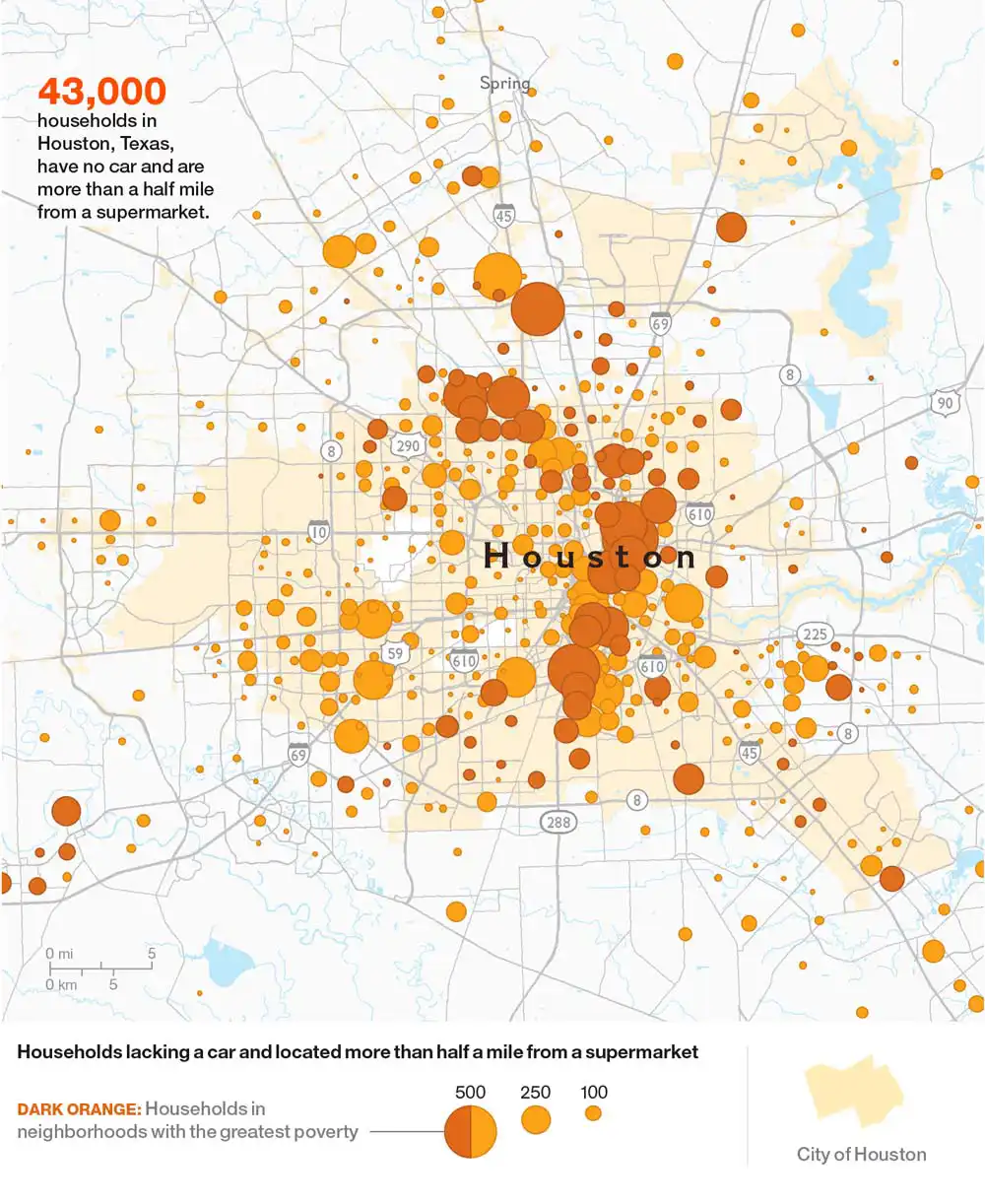

According to the The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020 study…

In addition to lack of access and availability, lower income communities are saturated with heavy advertisements and marketing efforts directed toward fast foods and unhealthy snacks. “Outdoor ads (on benches, billboards, and storefronts) for unhealthy products of all types, including cigarettes and alcohol, are more likely to be in areas with a higher proportion of minorities and low-income individuals.” Source 1 Source 2 Unhealthy food is not merely the only physical option, but it’s often the most common narrative they’re being fed.

Karen Washington explains how…

Food apartheid looks at the whole food system, along with race, geography, faith, and economics. You say food apartheid and you get to the root cause of some of the problems around the food system.

For example, 276 tribes receive food from The Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) that provides USDA foods to income-eligible households living on Indian reservations. Take a look at the 2021 list here. Other than a few frozen or dehydrated items, all fruits, vegetables, chicken, milk, and beef, are canned. Many canned fruits are loaded with sugary syrups, whereas excess sodium is the main concern in canned vegetables. There are too many people not having access or availability to healthy and fresh produce, whether they rely on a diet of canned foods from governmental food distribution programs, or simply don’t have transportation or income to afford fresh, nutrient rich produce.

03

PERFECTION COMPLEX, ALL YEAR ‘ROUND!

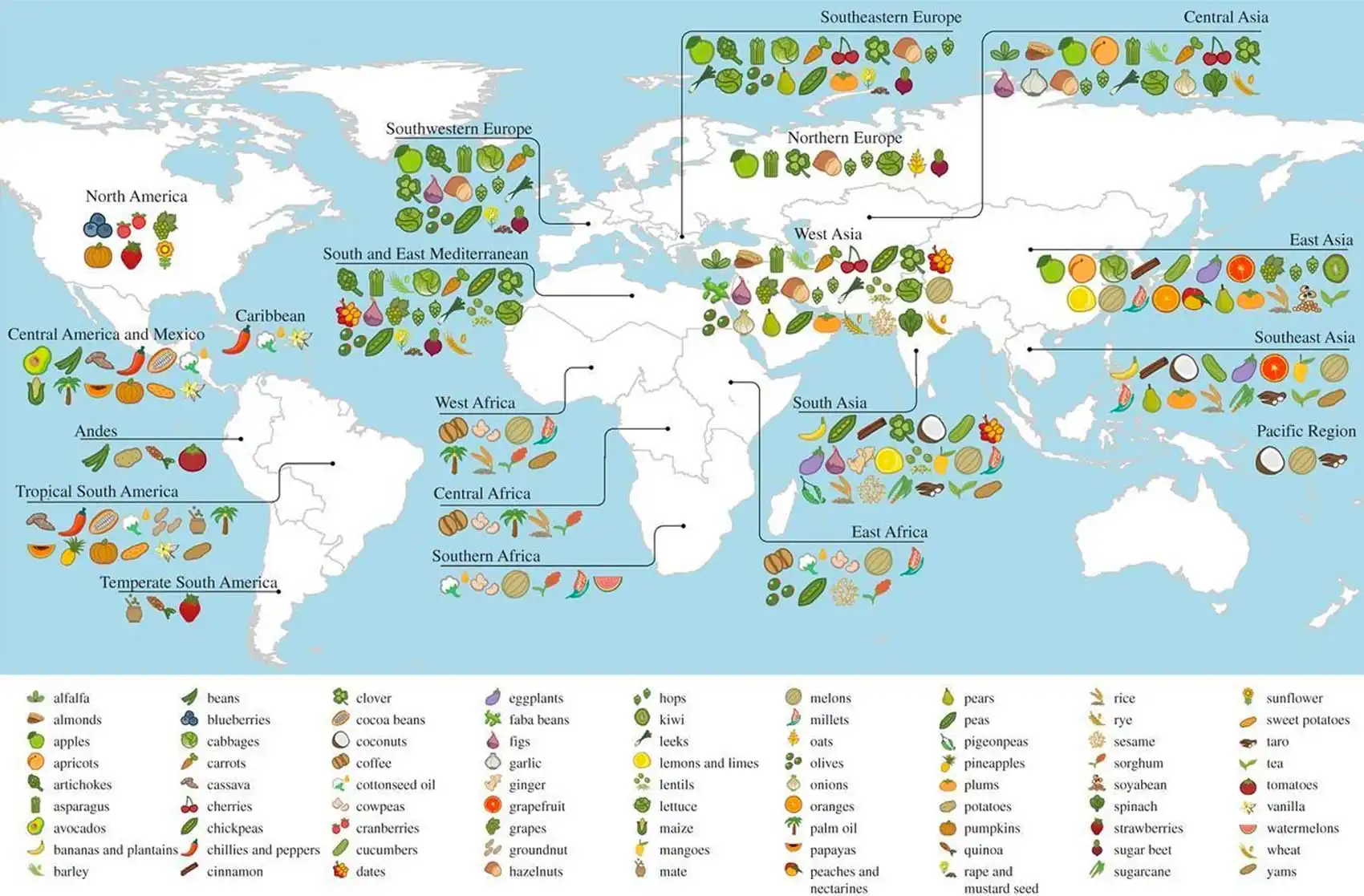

Typically in more developed economies, the conventional and globalized systems have overpowered the local food systems, further distancing us from the seasonal and indigenous varieties of the very landscapes we live in. No matter what US-based supermarket chain, it’s expected to find food that has travelled thousands of miles; grapes from Chile, bananas from Ecuador, wheat and tomatoes from China, etc. Source Consider how time in transit and travel accommodations can impact vital nutrients compared to freshness of locally sourced foods. According to a study at Montclair State University, brocolli’s vitamin C content was cut in half when shipped out of the country compared to when it was locally sourced. Source

How can we avoid falling into the unconscious act of buying produce based on the prevailing cultural beliefs around perfection? And how can we catch ourselves from expecting to have produce like tomatoes or mangos all year around? If you have the privilege and opportunity, get to know your farmer so you can build a relationship and trust in their agricultural practices. This will also inform you on what foods are in season and which you should be eating based on availability. Beyond faith in the farmer, work on developing your flavor profiles and palates; you should be able to taste the difference. If you’ve tried a store bought tomato versus home-grown, you know the taste is incomparable.

NUTRIENT DENSITY TESTING

Organizations like the Blue-Blanc Coeur in France, and the US-based Rodale Institute, Rhizoterra, and BioNutrient Food Association (BFA) have begun to analyze nutrients in the food we eat. This will provide transparency for healthy soils, plants, and animals, ensuring the end consumer is eating a superior product, in addition to providing farmers with best suggested practices.

In 2018, the BFA conducted their first study pulling from 648 samples of carrots from 50 unique stores and 48 farmers/gardeners. They found immense variation from one carrot to another; the antioxidant value of 1 carrot equated to the antioxidant value of 90 carrots grown elsewhere. That’s a 90:1 variation in the nutritional value of carrots (in terms of antioxidants)! For polyphenols, the variation was as high as 200:1; that means you would have to eat 200 carrots from one field to get the same nutrients out of one carrot grown elsewhere.

The goal of nutrient density transparency is to encourage agricultural practices that place nutritional quality at the heart of its concerns. Simultaneous with the unfolding scientific findings and home measuring systems (like the Brix meter or calorimeter), consumers can develop a palate for taste and a sensitivity to how certain foods make them feel. Beautiful flavors in produce coincide with high nutritional value. The same aspects of the plant that give it high nutrition, also give it the best flavors and aroma.