The Perils of Plowing

By: Farmer Greg Reese + Leia Vita Marasovich

What is Tillage?

Since the early 1900s, tillage has been a conflicting debate. The term tillage is defined as the agricultural preparation of soil by mechanical agitation of various types, such as digging, stirring, and overturning. Examples of human-powered tilling methods using hand tools include shoveling, picking, mattock work, hoeing, and raking. Tilling the ground is a management technique that can be used if/when necessary under the right circumstances. This technique breaks up the ground and loosens it, so that new plants or seeds can be planted. The process of deep tillage also kills the weeds that have grown, which further prepares a space for growing new plants. With certain crops, like potatoes, tillage is required for harvesting.

Minimal or light tillage can be done with a rotary power harrow or tilther. These tools loosen only the top 2 or 3 inches of soil without inverting deep ground. Although this allows deep soil to keep structure and biology, the top few inches still loses biology and structure. The benefit of loosening the top layer of soil is so that seeds can be sown directly into loose soil.

Tillage can be used effectively and in certain situations. Deep tillage below 4 inches is a short term solution, but can have long term consequences. Yes, breaking up the hard dirt into finer particles helps loosen the soil, but once these fine particles settle, this newly prepared soil becomes more compact than what it was previously due to gravity, rain, vehicles, tractors, animals, and people. Compact soil inhibits drainage, makes it difficult for roots to grow, and doesn’t retain moisture.

Tilling destroys weeds and prepares a space for growing. However, in the process of killing weeds by tilling, more are created! Some weeds spread by their rhizomes (root nodes that grow stems) so when they are ripped apart they actually spread further. Also weed seeds that are dormant below the surface are then brought to the surface through tilling, allowing them to germinate and populate an area. The short term benefit of quick weed removal actually results in more weeds over a longer period of time.

Soil biology, which is essential for plant growth, is lost due to tillage. This is because when the soil from 6-12” down is uplifted to the surface, the soil is then over aerated and exposed to UV sunlight, both which kill the soil microbiology.

Another negative side effect of tillage and the ploughing system is the inefficient use of time, energy, and fossil fuels. If a farmer tills, it’s important to restore the microbiology via cover crops or microbial inoculant, in addition to offsetting the fossil fuels used with gas powered engines.

The soils of our Earth represent the largest terrestrial pool of organic carbon. Source But with intensive agriculture activities like plowing, intensive grazing, and deforestation, this atmospheric pool seems to be compromised. Source Although we don’t know exactly how much soil carbon is affected and to what degree, there have been noticeable differences from various studies in soils that have been tilled over a long period of time versus no-tillage or short period tilling. Source The promotion of less intensive tillage practices and no tillage can mitigate negative impacts on soil quality and can preserve soil organic carbon (SOC). Source Over-tillage has diminishing returns over time because the soil degrades and becomes less fertile, causing more costly inputs like fertilizers and chemicals.

Prior to European settlement in North America, land-based peoples did minimal soil tillage with natural, low impact tools. They created a variety of handheld digging sticks using natural resources, such as thick mollusk shells or bison shoulder blades. It wasn’t until the 1930s, that the U.S. imported the first rotary tillers that were Swiss-designed and German-made. Source

“Most European settlers managed their soils by using the same methods they implemented back in western Europe. They cleared forests, applied fertilizers and lime to the acidic soils and plowed, harrowed and cultivated what’s now the eastern United States by hand or draft animal-pulled implements.” Source With these practices and the humid and rainy climate, soils began to lose fertility and erode. Between the American Revolution and the Civil War, people were moving west in search of richer soils in the prairies of the Midwest and Great Plains, while the northeastern farms were growing back to forests.

The Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was caused by several economic and agricultural factors, including federal land policies, changes in regional weather, farm economics and other cultural factors. Source

Storytelling in the Dust Bowl

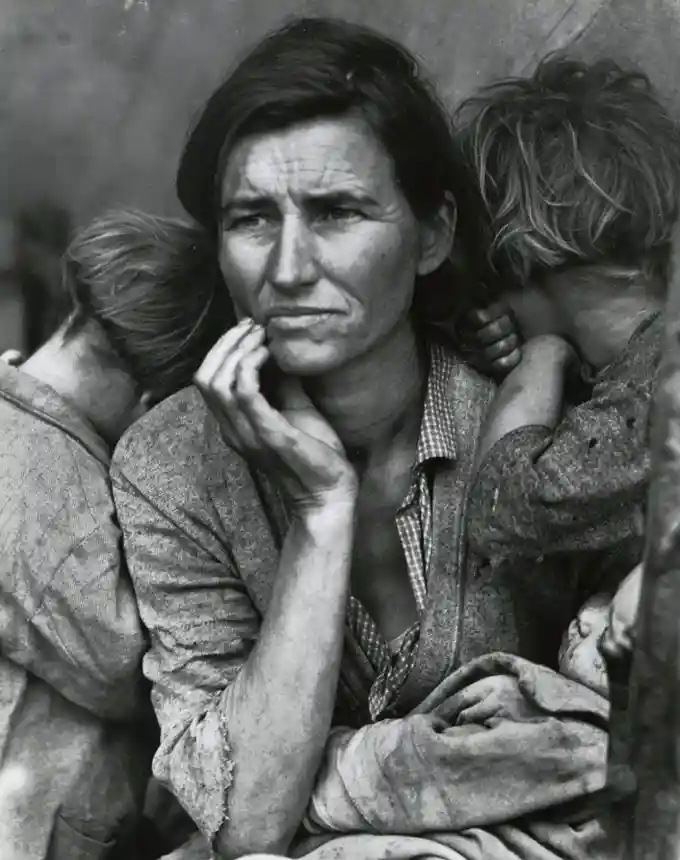

In 1936, Congress and the New Deal acknowledged the impacts of plowing on marginal lands. Between 1935-1943, the Farm Security Administration (FSA), developed by Franklin Roosevelt, produced the largest documentary project of a people ever undertaken, consisting of nearly 8,000 photos of Depression-era people. Source The FSA formed in 1937 to aid poor farmers, sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and migrant workers, with an emphasis on promoting soil conservation and resettling poor farmers to more productive land. To highlight the reality of this time and promote the governmental efforts being done to help farmers, the FSA had a photographic unit, called the “Historical Section” which commissioned a handful of photographers like Dorothea Lange, Jack Delano, Walker Evans, and others, to travel the country documenting the impacts of the drought and economic depression, mainly focusing on farmers and migrant workers. Source | Source Pare Lorenz made the first documentary of this issue, called “The Plow that Broke the Plains.” This film was watched by audiences across the US and received widespread critical acclaim. Source One image that exemplifies the plight of migrant farm workers during the Great Depression was the photograph by Dorothea Lange called Migrant Mother. Out of the documentation efforts of this time emerged a new body of work by individuals loosely called documentary photographers. Source Documentary photographers had a socially-minded task at hand, usually working for the U.S. government to depict raw, unfiltered realities of the time through photographic documentation.

U.S. Government Soil Policies

In addition to the storytelling efforts sponsored by the FSA, the Soil Erosion Service (SES) was formed in 1933, with soil expert Hugh Bennett in charge. The agency supported farmers by demonstrating soil conservation methods in watershed-based areas. Bennett wanted to have a stronger legislative foundation around soil conservation, so by 1935 he successfully promoted the passage of the Soil Conservation Act that called for changes in plowing techniques, strip cropping and shelterbelts to cut down on wind erosion. The Soil Conservation Act called for “the protection of America’s soil to preserve natural resources, control floods, prevent impairment of reservoirs, and maintain the navigability of rivers and harbors, protect public health, public lands and relieve unemployment…” Source Hugh Bennett, known as the “father of soil conservation,” was one of the main advocates and researchers of soil science starting in the 1920s until his retirement in 1951. Source Bennett proclaimed…

Now that we’ve seen the extreme impact over-plowing is capable of, we must apply these lessons and principles to farming techniques today. With an extractive mindset based on yields and an insensitivity to the quality of soil, the Dust Bowl has taught us many lessons, but one in particular stands out… with no life in the soil, there is less life on earth.

First off, a common understanding in the agricultural world is that if you are a “no-till farm” that means that you would use herbicides to kill the weeds. This does NOT have to be true. There are many alternatives to herbicide use and tilling that can deliver the same results in a holistic and ecological manner. Using cover crops like Daikon Radish have roots that can break up hard clay, aerate the ground, and add organic matter. This process takes longer than tilling with a tractor because it takes a few months for plants to grow. So, if you have the time and space, it can have great results long term. Weed prevention can be used without herbicides (a topic we will discuss in detail on a later blog). Also, using a broadfork allows for aeration in the ground without disturbing the soil structure. The roller crimper is another alternative that can be used for no-till farming. Research has shown that consistent no-till practices will eventually return the soil, water, and biological system back to its native fertile soils.

Using tillage strategically can be beneficial for an initial quick result. For example a ONE TIME tillage can be done when initially preparing a growing space for row crop production or garden. Deeper tillage of 6-12 inches can be used one time to mix in organic matter or minerals to amend the growing area for planting. This makes a permanent bed that doesn’t get tilled, mixed, or moved – it stays as a permanent row. Tilling one time can create a deep hardpan (hard compacted layer underground) which inhibits drainage, but soil biology and structure will recover and grow in time. Again, this speeds up the mixture process, although cover crop roots will do this same job in a longer period of time.

What works for you in your climate and land may be different from the techniques and tools I’m using. There’s no perfect answer to till or not to till; we are continuously learning how to farm and grow food in an ecological manner. The techniques and ideas that I’ve written about are based on my own personal experience through trial and error and learning from others, which means there’s always room for growth and improvement! Test things out for yourself, talk with other farmers, and focus on progress over perfection.

It is estimated that over 125 million acres of farmland topsoil had been lost during the Dust Bowl winds. Source Topsoil erosion, intensive over-cultivation of marginal lands, failing crops, 2.5 million displaced people homeless and jobless…what did we learn from all of this? The Dust Bowl exemplified the social, economic, and environmental impacts caused by a series of short-term decisions coupled with a dissonant relationship to land. It caused the government and farmers to pivot towards soil conservation and preventative soil erosion practices. The Farm Security Administration made a public effort to inform and express the reality and activities of this time through documentary photography, in addition to making legislative initiatives like the Soil Conservation Act. In farming, it’s important to take a proactive and preventative approach versus the retroactive and reactionary. Although something may work temporarily for a quick-fix solution, it’s important to look at its sustainability for the long term- what foundation are we leaving for the next few generations?

In using the term regenerative agriculture, we return to, recognize, and honor the wisdom of ancient practices that restore and regenerate the earth’s ecosystem, rather than degrade it. As Reginaldo Haslett-Marroquín says…

At any given moment we are either regenerating land, or degenerating it.