Restoring Reverence to the Origin

Culture in Agriculture

Come With Us on a Journey to Ancestral Waters

A journey through the sacred waters of Xochimilco—where women, soil, and ancestral farming traditions reveal a living story of reciprocity, resilience, and return.

Culture in Agriculture

Come With Us on a Journey to Ancestral Waters

A journey through the sacred waters of Xochimilco—where women, soil, and ancestral farming traditions reveal a living story of reciprocity, resilience, and return.

Origin Stories

Restoring reverence for origin through listening to the stories held by the land and its First Peoples.

en

To look forward, we must look back—to the beginning.

Origin Stories is a reverent exploration into the ancestral relationships between people and place. It invites us to listen deeply to the stories carried by the land and the First Peoples who have walked it for millennia.

In this series, we will delve into the origin stories of place and people for each feature that we release here at Farmers Footprint.

These stories illuminate the ways humans once lived in right relationship with nature—how food was not only cultivated, but honored; how culture and ceremony wove through the daily tending of land and kin; how reciprocity shaped every gesture toward the earth.

Centered on the knowledge and enduring presence of First Nations communities, Origin Stories pays particular attention to ancestral foods and the intricate webs of nourishment—ecological, cultural, and spiritual—they sustain. These stories are not relics. They are living legacies.

Through this series, we are invited to slow down and witness the nature present in our own lives—the rivers, birdsong, grasses, and seasons—and to imagine how life once flourished in reciprocity here. With humility and care, we ask: how might we honor these ways in our present-day lives?

Origin Stories asks us to restore reverence for origin. To acknowledge, with deep respect, the First Peoples of the lands we inhabit. And to see food not as commodity, but as connection—to earth, to ancestry, to community, and to the sacred cycles that sustain life through highlighting the original agricultural systems of each place.

Ancient Teachings for

a Modern World

An invitation to embark on a journey inward, guided by the echoes of time-honored insights, to rediscover the profound knowledge that resides within us all.

en

Elders carry with them wise stories that hold the power to reconnect us to the world and each other, reminding us that we are all of this earth… By embracing their wisdom and honoring their legacies, we can weave together a future that will endure. Their timeworn knowledge, like a river of ancient truths, flows into our hearts, offering us both guidance and resilience in the face of the unknown.

Through conversations and dialogues with indigenous elders across the globe, we bridge ancient wisdom with modern science. Honoring our roots to cultivate our future: this is a space to explore regenerative practices through ancestral paradigms.

By sitting with Elders from different cultures around the world, and engaging in their stories, we intertwine ancient wisdom with modern science to deepen our bond with the Earth. In this series, we will become accustomed with sacred insights that can illuminate our path towards a regenerative future.

The Vital Role of Elders in Preserving and Sharing Ancestral Wisdom

Written by Jessie Gardner with collaborator Marilu Shinn who connected us to the featured elders Don Sebastian Sucli and Don Andres Apaza

No matter where we are in the world, we wake each day to profound uncertainty, as wars rage and our planet withers. We find ourselves adrift in the isolating currents of individualism, severed from nature and community. And in our forgetfulness, we have overlooked the wisdom of our elders—the cornerstones of our society who hold invaluable stories, songs, rituals and lessons. With a bird’s eye view, they have the unique ability to weave together the threads of ancient and modern knowledge, embracing complexity and illuminating our path forward. In their stories and teachings, we can find the guidance and clarity we so desperately need to navigate these turbulent times.

There has never been a more important time in history to listen when our elders speak.

First, I want to acknowledge this conversation would not have been possible without facilitation from Marilu Shinn who has nurtured her relationships with these elders and community for over 20 years, and Yuri Flores who supported translation from their native Quechua language.

The honor of speaking with Don Sebastian Sucli and Don Andres Apaza is met with deep gratitude for this weaving.

Meet the elders

Nestled among the rugged peaks lives Don Sebastian Sucli, an 82-year-old Pampa Mesayoq and revered keeper of Earth Medicine Wisdom. His journey into medicine began at the tender age of eight when a bolt of lightning struck him, marking him as chosen by the Earth and the forces of Nature to become an Alto Mesayoq, a high-level bridge between the realms of the living and the spirits.

This calling was met with resistance from his family, especially his father, who dreaded the arduous path and the many sacrifices demanded of a high priest, including a shortened life.

In alignment with the Andean path, he became a healer and medicine man deeply attuned to the forces of nature. Over the years, he learned to cure diseases and restore balance by engaging with the Earth’s energies. As an Earth Ceremonialist, he has dedicated his life to preserving and passing down the wisdom and ancestral rites of passage of his Incan forebears. His mission is to awaken the seeds of Earth keepers in those who seek the Andean Ancestral Path. It is the strength and power of the pulse of the Earth that helps them understand disease at an energetic and spiritual level, which Marilu refers to as a ‘high art’.

“Their way of living is a constant prayer, giving in service, joyful constantly chewing coca leaf – the intermediary between them and the land and the spirit world”

– Marilu Shinn

Not far from Quico, in the Andean community of Hatun Q’ero lives Don Andres Apaza, an esteemed Incan Earth Steward and farmer. From a young age, Don Andres was immersed in the sacred ways of Earth stewardship, learning to live in harmony with the land that nurtured him. His journey took a significant turn during his teenage years when he was formally initiated as a Paqo Mesayoq, and he has devotedly followed the spiritual Andean path ever since.

A pivotal moment in Don Andres’ life was when he received teachings and initiations, known as Karpays, from the revered Alto Mesayoq, Don Manuel Quispe. These sacred teachings, imparted at various holy mountains, deepened his understanding and commitment to the ancient Incan ways.

Now, at 63 years old, Don Andres continues his work with an open heart, welcoming seekers from around the globe who wish to learn the Andean ways of Earth medicine and stewardship. His home in Hatun Q’ero is not just his place of residence but a beacon of ancient wisdom, welcoming those who come with a genuine desire to serve their communities in sacred reciprocity and to forge a deep connection with the Earth and its timeless traditions.

The cultural ethos of Don Sebastian and Don Andres is deeply rooted in community, reciprocity and relationality with nature.

COMMUNITY AND RESILIENCE

“To live ‘in community’ is to have a circular way of thinking. When someone is lacking resources, the community is always willing to extend a hand and support each other. This stems from the necessity imposed by the harsh environment of the high Andes.”

– Don Andres

“It is our reliance on the collective work and community that has allowed our existence to carry forward and to survive everything that has been happening over the last 500 years. Because we live in such remote and isolated places up in the mountains, if we emphasized individual needs, we probably would not be alive today.”

– Don Andres

“Collective love and care has built our resiliency, which is the strength to carry forward and maintain the ways of our ancestors as sacred and intact.”

– Don Andres

“In today’s society with globalization and the continual erasing of our ways through colonization, I see how important it is for us to keep preserving and embodying our ancestral, sacred wisdom. I see how the youth in our communities are feeling the inner conflict of retaining their wisdom but also not wanting to be left behind.”

– Don Andres

PRESERVING AND EMBODYING SACRED WISDOM

His pensive gaze gives way,expanding with his whole heart as he emphasizes that they, as elders, are the embodied wisdom of their ancestors. Having a deep reverence for ancestral knowledge and the community helps them carry forward with their ways of being and living.

Earth as mother

Their Cosmovision tells the story of a worldview composed of three distinct worlds. First, there’s the Uhku Pacha, the underworld and hidden realm beneath our feet. It’s a place of roots and healing, symbolized by the serpent. Next, is the Kay Pacha, our ordinary world. This is where we live and breathe, the realm of Pacha Mama, a world embodied by the strength and inner discernment of the puma. Above us, there’s the Hanaq Pacha, the upper world, soaring in the lofty heights of the condor’s flight, where the spirits dwell and we can seed the possibilities for a new shared future.

“We relate to a multi-dimensional world with the upper, middle and lower worlds. Our deep connection with the earth mother teaches us all about life. We have an ongoing relationship with her. We speak to her, and she replies, and when she replies, she teaches us the roots of modern day society’s illnesses and diseases that we understand at the soul level. This is why it is so important to retain our body of wisdom, because we can help people heal from modern day diseases because they originate from the disconnection with the land, from hyper-individuality and lack of reverence.”

– Don Sebastian

“The fast pace of life and disconnected way of living in the city can cause confusion of self and community values.”

– Don Sebastian

Through witnessing their connection to the earth we are tapped on the shoulder and asked do you remember this way of life from which we all come from, Indigenous to earth, when we could hear her and she could hear us? When we cared for her and she cared for us?

The Q’eros believe the imbalance we are experiencing in our modern world comes from this disconnect in communication and relationship with the ancient. Don Sebastian says that one way we can reconnect this broken channel is through the act of spiritual payments.

He says the act of giving back to the mountains, and nature as a whole, is critical to life on earth.

“The origins of bringing offerings to the earth is like the analogy of the human body. If we don’t have proper nutrition, we will be depleted or nutrient deficient. We need to feed our physical body, just like we also need to feed the Earth’s body so that she can also be vital, healthy and well. How can we expect our food to be nutrient dense if we lack respect for the body of the Earth? So by bringing offerings to the Earth, we are paying her in reciprocity for everything that she provides to us.”

– Don Sebastian

RITUAL & RITES OF PASSAGE

The short answer is through the sacred coca leaf and rites of passage.

The humble coca leaf is a small but potent vessel, fostering connection to Mother Earth. The Andean people have long revered the sacred practice of offering three coca leaves, each one an act of tangible prayer bridging the three realms of existence. These leaves are more than mere botanical specimens; they are the sacred messengers of the Andean Cosmovision and because they walk miles to tend to the land, the coca leaves provide them stamina and vitality.

Each leaf acts as a conduit, a tiny bridge across the spiritual divide, allowing the elders and shamans to traverse the multidimensional upper, middle and lower worlds to deliver vital messages. Through this practice, the coca leaves become more than pure offerings; they are the threads that together weave the tapestry of life, connecting the earth to the heavens and binding us to the sacred rhythms of the cosmos.

“The coca leaves act as conduits between our intentions and the land.” – Don Andres

For them, rites of passage are also central to the cosmovision and right order of things.

The birth of a newborn being introduced to the community for the first time, the rhythms of planting and harvesting, the initiation into healing roles, the transition to elderhood, and the arrival at death are all significant milestones,, each marked and honored through unique rituals and rites of passage.

“Every rite of passage opens communication with the realm of the spirits which includes the earth and the seven apus (mountains). Once you receive them, you enter a completely different way of relating to the earth mother, but also to the mountain spirits who give transmissions and initiations. In exchange for the devotion of our pilgrimages to the mountains to receive wisdom and the ability to heal others, we receive health and blessings.”

– Don Sebastian

When it comes to the land and animals they steward, constant rites of passage are brought to life. They bless the livestock, crops and harvest with a prosperity rite of passage called Pago a la Tierra.

“In the Pago a la Tierra, they first bless the hands of the farmer and the land with prayers, breath and with offerings of seeds and flowers and chicha (a traditional Inca beverage made with corn) asking permission to the Pachamama to plant the seeds and ask for abundance and right relation with the land, the soil and the crops.”

– Marilu Shinn

Nustas carry medicine and they either work with the left side and the right side. There are women who carry more of the right side medicine, which is the earthkeepers way and can also perform healings. Then, there are women who carry the left side, which is like preserving the deeper knowledge and wisdom of the ancient cosmovision.

“In nature, the energies of the feminine are everywhere. And in the sacred mountains in the waters, there is this analogy to the female body. By honoring and initiating women’s new steps into this path, it brings more balance between the masculine and the feminine, the duality of this world.”

– Don Andres

Death and dying, are processes deeply respected in this tradition, and are marked with an equally powerful rite of passage. This rite may involve elaborate ceremonies where the physical body is separated from the energetic body and the soul. Trained healers perform energetic maneuvers and prayers on behalf of the deceased person during this rite.

An invitation for earth keepers

With that final invitation, we lay these thoughtful questions at your feet to explore after reading this feature:

“If more people are receptive and willing to listen and to serve from purity, we can begin to be an allyu (all life around you, a network of families with a common ancestor) again, which will bring much needed healing and repair to the web of life, the earth and to our relationships. This is how the ancestral wisdom will carry forward for generations to come.”

– Don Andres

With that final invitation, we lay these thoughtful questions at your feet to explore after reading this feature:

- Are you connected with local elders in your local community?

- What are the most valuable lessons you’ve learned from elders?

- What would the world look like if we held a reverence for elders?

- How would your life look different if communal values were prioritized over individual values?

- How do you communicate and relate to the earth?

- How do you engage in rites of passage in your life? Do you identify a link between them and your wellbeing?

- Do you feel called to experience the culture, rites of passage, and Indigenous ways of the Q’ero people? If so, please reach out to us directly and we can connect you to their community.

Reconnecting With Our Indigeneity: We Are All Ancestral

The Story of Our Return to Culture through Land, Lineage, Food, and Story.

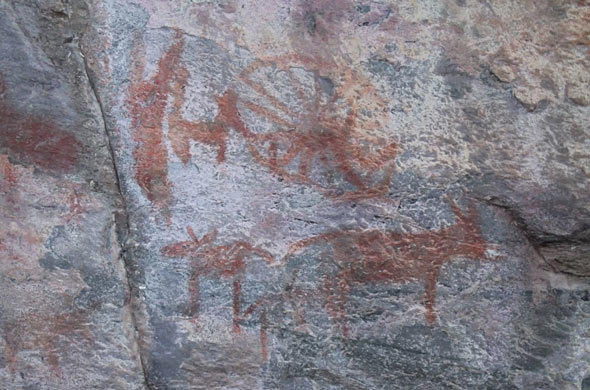

The history of our ancestors was not written in books. It was spoken, sung, and carved into the landscapes and spaces that held their lives. Stories lived in the words of our elders, in ceremonial songs that were carried through generations—in oral traditions that told us of creation stories and lessons of the lands that sustained us. Across cultures, storytelling binds us to place, to people, and to purpose. These stories tether us — to the earth, to one another, and to the eternal wisdom that reminds us we are a part of the living world. They are not just memories of the past; they are living instructions for how to move forward in reciprocity and respect.

To tell a story is to plant a seed — one that may grow into understanding, into action, into remembrance. Through stories of our lands, we carry the knowledge of our ancestors into the future, ensuring that the roots of our culture remain unbroken. And like seeds in the soil, stories are always waiting — for the right moment, the right listener, the right heart — to listen, to learn, and to grow once more.

Maria Elena ‘Mia’ Lopez, a Chumash Elder, university professor and wisdom keeper, speaks to this sacred remembering. She reminds us that we are all indigenous to somewhere, that our roots are not lost but waiting to be remembered. ‘A lot of people say we are all indigenous to somewhere, and we are,’ she says. ‘If you know about that place, that’s how you reconnect. If you know deeper about who you are, who your parents are, your grandparents and so forth — know your lineage, know where you came from — it’s the same as knowing history. We know history, why? Not because we can change it, but if we don’t know it, we can’t move forward in a better way. And so if you know your history, your people, your lineage then collectively, we can move forward together in a good way.’

“I don’t want you to go home, because we are all now home together,” she says, her voice steady as the earth itself. “But I do want you to know where your ancestral home was. I want you to know why your people thrived there, why they loved it, what was in that land that brought them health and family and community.”

This is an invitation—not to retreat, but to return. Not to claim, but to remember. The land does not ask us to possess it. It asks us to be in relationship with it, to understand that where we stand now is woven with the places our ancestors once called home.

I have spoken with elders from many indigenous traditions, and every single one of them has told me the same thing: The time is now. The time to remember that we are all indigenous is now. Every human being is indigenous to this earth, yet many have been severed from the knowledge of their origins. If we do not know where we come from, how can we ever know how to truly belong? But if we trace our lineage, if we seek out the lands that nurtured our ancestors, the food they ate, the ways they spoke to the earth, we will find that indigeneity is not exclusive—it is our birthright.

As a Māori woman, I carry the understanding that my people, like all peoples, have been gifted the wisdom of those who came before. Our ancestors left us knowledge, practices, and principles so that we may come together and move forward in unity. The more I delve into Regenerative Agriculture, the deeper I am reminded of our ancestral food systems. This wisdom was not given to be hoarded or lost; it was meant to be lived, shared, and remembered. Our tūpuna (ancestors) understood reciprocity, how to listen to the land, how to cultivate abundance in a way that sustained generations.

Many of us today are disconnected, not just from our ancestral lands, but from the very understanding that we belong to the earth, not the other way around. Colonization and industrialization have pulled us from the cycles that once sustained our people. The knowledge that once passed from grandparent to grandchild, through hands in the soil and songs in the air, has been severed. And yet, as Mia reminds us, the memory of that relationship still exists—it is waiting for us to listen.

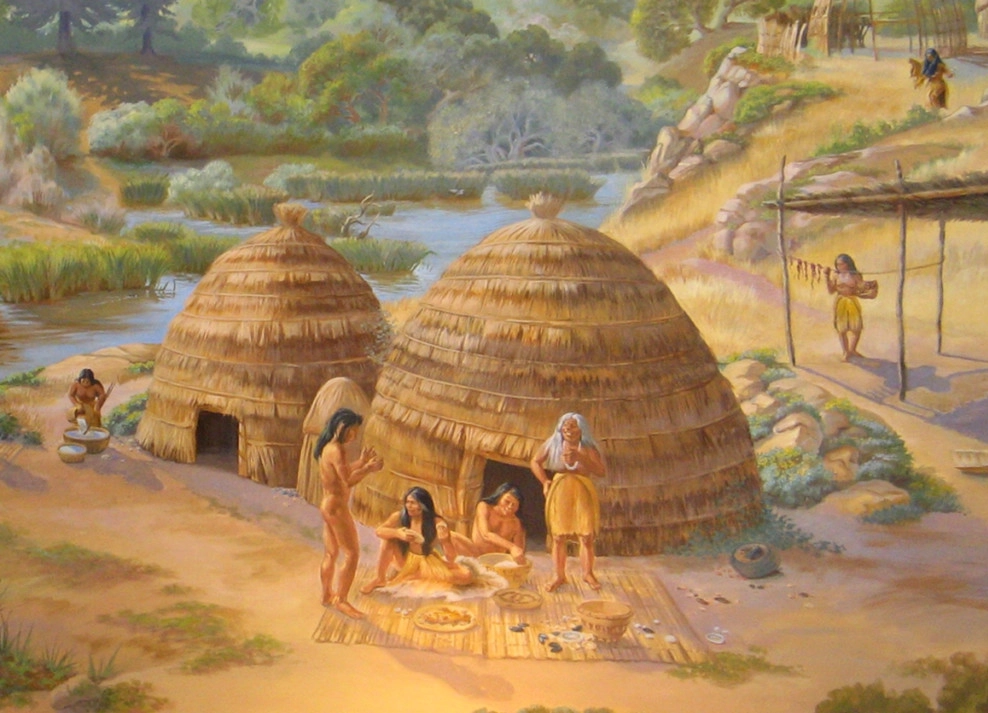

She speaks of Syuxtun, now renamed Santa Barbara, and how her people lived in deep harmony with the land. “Our landscape here was abundant because we allowed our plants to live together. The Three Sisters—corn, beans, and squash—grew as companions, supporting and nourishing one another. But colonization brought monocropping, and in severing those relationships, the land suffered.”

This severance is not just agricultural; it is cultural, spiritual, and systemic. The shift to extractive farming mirrored a broader shift in human consciousness—a mindset of control, ownership, and dominance over the natural world. But the land has not forgotten. Regenerative agriculture is not a trend, not a new solution, but an old knowing. It is the remembering of what has always been true: when we farm with the land, rather than against it, abundance follows.

Dr. Zach Bush calls this moment one of profound imbalance—where chaos stretches from the cellular to the societal to the planetary. Yet within the disorder is a promise of renewal. “We live in a universe that practices centropy—the emergence of order from chaos. What will bring us back into balance is the moment we just give witness to beauty. He reminds us that for 10,000 years, human economies have been built on scarcity. Nature has never operated this way—and we must return human economies to the value systems of the earth itself.”

Zach also speaks of a deeper cultural shift that must take place. “If we’re really going to change everything, it’s going to be the culture of food. NANA is our description of this culture of food that will be birthed. It is going to be the culture of food that makes the regenerative story become relevant and palpable in every single home in this world—where we start to eat the future that we want to live in.”

Storytelling, then, is not merely a tool—it is a path. It is how we remember, how we re-story ourselves back into balance. As Oliver English puts it, “We have the solutions already. This is not about inventing something new; it is about a realignment. This is going back to ancient and indigenous wisdom, to the practices that have sustained life for generations.”

We must embrace our ancestral wisdom, and those that hold it, and bridge our current science with ancient truths. This is not about discovering new technologies but reclaiming ancient principles that have been disregarded by the industrial mind and movement.

Mia listens to these words and reminds us of the power of community. “We are not alone. If everything we do, we do with ten others in mind, we will do better. And we must choose to move forward with positivity. No more narratives of despair—we turn that story around. We start small, but we start. Even if it’s 5%, even if it’s 1%, it is something. And we do it together.” As the human species indigenous to this earth, we are truly in this together.

Beginning, after all, is everything. The first seed planted, the first story told, the first step taken back toward reciprocity.

This is what re-story-ation looks like. A remembering. A return. A seed planted deep in the soil of our collective knowing, waiting for us to witness it, to learn from it, and to let it grow for future generations to come.

It is time to remember the culture in agriculture, through food, story, and ancestral wisdom.

Written By: Briar Rose, Director of Storytelling

Watch the Dialogues Below to Explore the Story of Our Return to Culture through Land, Lineage, Food, and Story

‘Re-story-ation’ – Stories of Place and People

Origin stories of people and place through culture & agriculture

en

By listening and staying curious, we engage in ‘re-story-ation,’ a healing of both land and spirit. We come to understand that the health of our bodies is woven with the health of the soil, that our well-being is bound to the well-being of all beings.

The deeper we go into Regenerative Agriculture, the more we come to understand that it is, at its core, a return to what has always been—traditional agriculture. These are not new ideas but rather the time-honored practices that have sustained communities for millennia, passed down from generation to generation. Long before industrial agriculture, our ancestors cultivated the land with deep reverence, working in harmony with natural cycles, honoring biodiversity, and nurturing the soil as a living entity. These principles—once the foundation of food systems worldwide—are now resurfacing within the regenerative movement, not as a trend, but as a necessary remembering. In this collective awakening, we are reclaiming the wisdom embedded in ancestral foodways, recognizing that the answers to modern agricultural crises have been with us all along, waiting to be embraced once more.

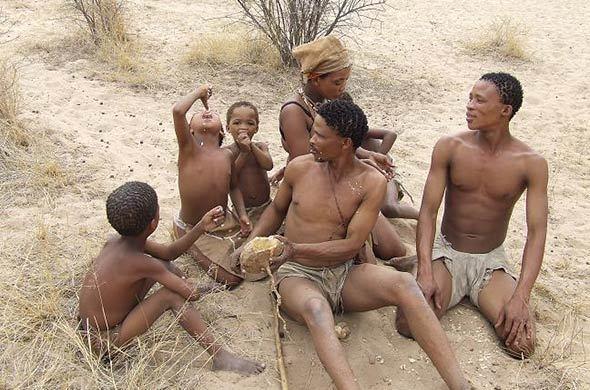

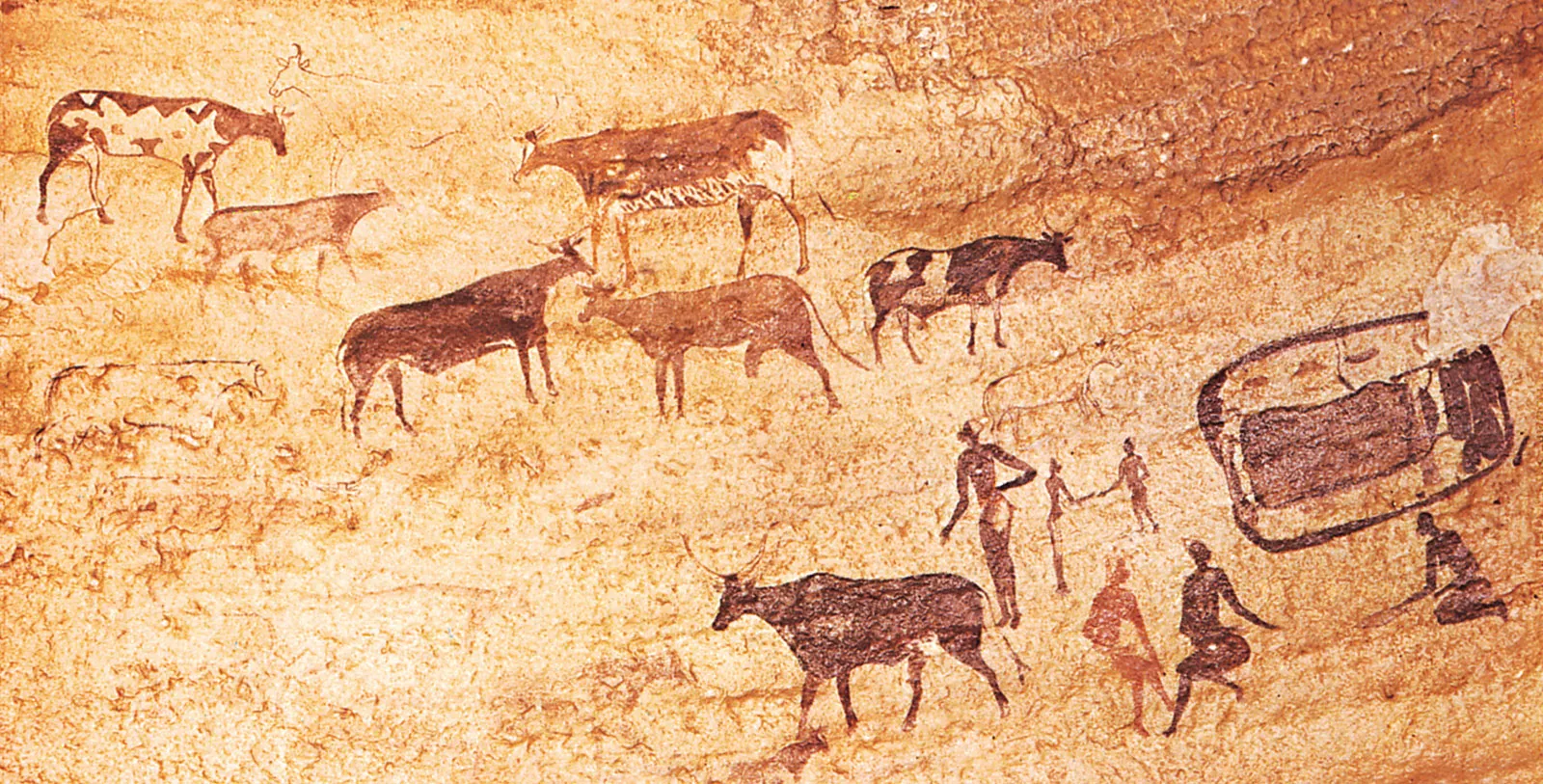

Angola

Indigenous name: no singular unified name as various indigenous groups inhabited the land before the Portuguese named it ‘Angola’

Indigenous peoples: Saan + Khoisan + Bantu Peoples

en

What is the indigenous name of that country?

Who were the original peoples of the land?

- Southern Africa’s first indigenous peoples have been referred to as the San. The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are the members of any of the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of southern Africa, and the oldest surviving cultures of the region (9).

- The San peoples were joined by the Bantu peoples, who introduced Agriculture.

- San Peoples → Bantu Peoples – the Introduction of Agriculture

How far back can we see the agriculture of this land?

What tools did they use?

- Both stone and iron tools were utilized for farming (3).

- Their introduction of iron tools led to increased food production and supported population growth.

- Iron-smelting technology was developed, producing more efficient agricultural tools like hoes for planting, weeding, and land clearing (3, 4).

What animals did they manage?

- Cattle, sheep, and goats.

What resources did they have available?

- Water Resources: Rivers and water sources were crucial for both agriculture and hunter-gatherer lifestyles.

- Forests

- Diverse wildlife: Including elephants, hippopotamuses, monkeys, giraffes, zebras, buffaloes, and various antelopes

Plant resources: The varied flora of Angola’s savannas and forests would have provided edible and medicinal plants. - Raw Materials: Woods, reeds, and animals (and, formerly, stone) are the main raw materials from which their clothing, carrying bags, water containers, and hunting weapons were made. For hunting they used bows and poisoned arrows, snares, throwing sticks, and sometimes spears.

The Bantu practiced slash-and-burn agriculture in forested areas (5).

- They created small clearings by cutting down trees and burning stumps and undergrowth (5).

- In savanna regions, they prepared fields with rows of earthen mounds (5).

- Planting typically began in April or May, coinciding with the first rains (5).

- Women and children often performed tasks like weeding and transplanting (5).

What were the staple crops?

- Staple crops: Yams, cassava, cocoyams, plantains, and bananas (5).

- Grains: Millet, sorghum, and rice (5)(3).

- Other crops: Beans, okra, onions, melons, and peppers.

What foods did they eat?

Examples of common foods include. wild game, beef, tortoises, crayfish, coconuts, squash, fermented grains (maize, sorghum, millet), okra, pumpkin, beans, goat, antelope, zebra, shellfish, fish, wild hare, lion, giraffe, snakes, hyena, eggs, bananas, yam,, cassava, sweet potatoes and wild honey, fermented milk (6).

What did they trade and who did they trade with?

The Bantu people traded several agricultural products as they migrated across sub-Saharan Africa including:

- Yams: This was one of the staple crops cultivated and traded by the Bantu (2).

- Oil palm products: The Bantu grew oil palms and likely traded palm oil and other related products (2).

Bananas, taro and plantains: These were important crops introduced and spread by the Bantu (1). - Sorghum and millet: These grains were cultivated and traded by Bantu farmers (1)(2).

- Dry rice: A variety of rice adapted to drier conditions was among their agricultural products (1).

Beans and groundnuts (peanuts): These were also part of the Bantu agricultural package (1)(2).

Other Agricultural Products

- Cattle and livestock: The Bantu people were animal herders and likely traded cattle, goats, and sheep (1).

- Iron tools and weapons: While not crops, these were significant trade items produced using their advanced ironworking technology (1)(3).

Trading Partners:

- Indigenous hunter-gatherer societies they encountered during their migration

- Other Bantu-speaking communities

- Non-Bantu agricultural societies

- Later, with coastal traders and Arab merchants along the Swahili coast (1)(3)

- The Bantu migrations facilitated the development of extensive trade networks across sub-Saharan Africa, exchanging these agricultural products and other goods like iron, copper, and ivory for salt, cloth, and other commodities (1)(3). This trade not only involved the exchange of physical goods but also agricultural knowledge and techniques, contributing to the spread of farming practices across the continent.

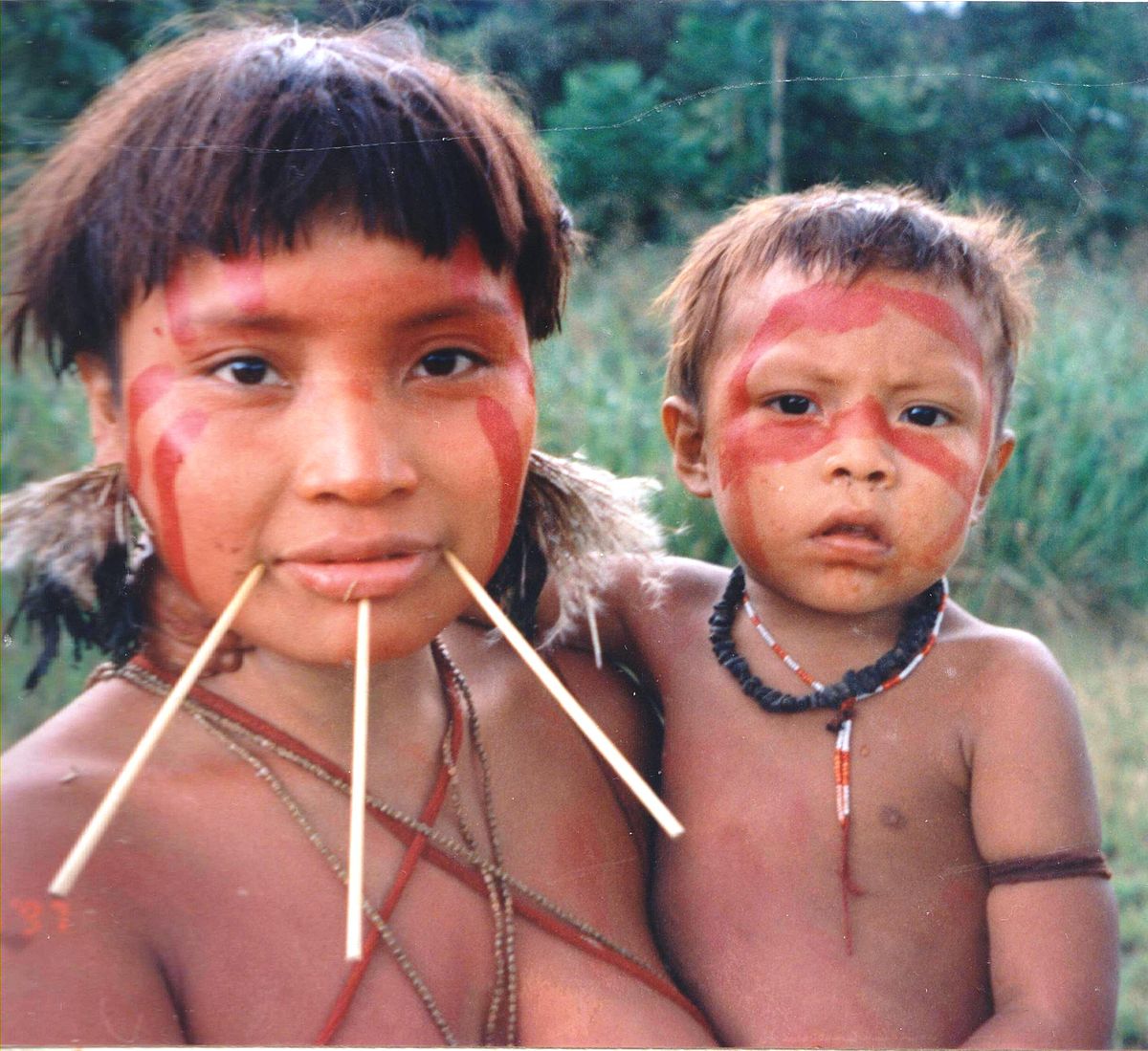

Brazil

Indigenous name: The land was inhabited by over 2000 indigenous groups with their own territories and names.

Indigenous peoples: Tupi + Tapuia (Jê) + Caribs + Nuaraque peoples

en

What is the indigenous name of that country?

Who were the original peoples of the land?

- Before European contact in 1500, an estimated 2,000 indigenous tribes and nations inhabited what is now Brazil, with a total population of around 2 to 3 million indigenous people (2).

- The two main indigenous groups were the Tupi and Tapuia (Jê) peoples (2).

- The Tupi occupied the coast, while the interior was inhabited by the Tapuia (Jê) peoples, along with Caribs and Nuaraque groups in parts of the Amazon region (3).

How far back can we see the agriculture of this land?

Agricultural practices varied among indigenous groups, with many combining cultivation with hunting, fishing, and gathering. Some groups, like the Tupi, practiced slash-and-burn agriculture and crop rotation (3). After European contact, some indigenous groups also adopted and cultivated introduced crops, such as coffee (7).

What tools did they use?

- Fire was used in swidden agriculture (slash-and-burn) to clear land for cultivation.

- Simple hand tools like hoes and digging sticks for planting and cultivating crops (8).

- Axes and Machetes (11)

- Mortars and Pestles (8)

- Bows, arrows, and blowguns for hunting.

What animals did they manage?

What resources did they have available?

- Diverse crop varieties

- Traditional heritage seed banks

- Wild harvesting

- Brazilwood

- Cotton

- Natural resources – fertile soil and access to rivers and streams were vital for irrigation and agricultural practices (12).

- Cultural practices – planting times were guided by lunar phases and seasonal changes, reflecting a deep understanding of ecological relationships (8).

- Communal farming – communities often worked together in agricultural activities, sharing knowledge and resources to enhance productivity and sustainability (13).

What were the staple crops?

- Staple crops – Cassava, corn, sweet potatoes, peanuts, Pumpkins (Jerimum), yams (Cará), bananas, and pineapples (3)(5).

- Other crops – Tobacco, beans, peppers (cumari), brazil nuts, cashews, cacao, açaí and other palm fruits (7).

What foods did they eat?

A traditional diet of indigenous peoples of Brazil consisted of staple crops, proteins, fruits, nuts and wild honey. Fishing and hunting were fundamental to the indigenous diet, with fish as a primary food source. Hunted animals included peccaries, tapir, monkeys, and birds like the curassow (5). Meat was often cooked in its own fat, enhancing flavor and preserving nutrients. Cooking methods varied, including grilling over an open fire, roasting on a wooden grid called “boucan” or “moquém, smoking, cooking in clay pots, and burying food underground (9).

- Staple crops – cassava, sweet potatoes, corn, bananas, pineapples

- Proteins – fish (pirarucu), game animals–includingcapybara, peccaries (similar to wild pigs), tapirs, monkeys, deer, and armadillos.

- Fruits and nuts – açaí, guava, passionfruit, wild fruits, berries, peanuts, brazil nuts, cashews.

- Traditional dishes – Wàt tynondem (baked fish wrapped in banana leaves), Karak’ kuréum (edible leaves of a variety of elephant ear plant), Onatji magarapa (corn cake).

What did they trade and who did they trade with?

Indigenous peoples in Brazil engaged in various forms of trade, both among themselves and with European traders, before and after European contact. Tribes traded with neighboring groups, exchanging goods like agricultural products, fish, game meat, and crafts based on regional specialties (14).

After European contact in the 1500s, indigenous peoples began trading with Portuguese settlers, who sought brazilwood and other resources. In return, they received European items such as metal tools, textiles, and firearms. The introduction of a cash economy altered traditional trade practices (14).

- Cassava and corn: Staple crops cultivated by the Tupi peoples and traded with neighboring tribes and European settlers (8)(15).

- Sweet potatoes: Widely traded across indigenous regions and with European settlers (8).

- Peanuts: Staple crops cultivated and traded by the Jê peoples (15).

- Tobacco: Traded amongst indigenous groups, as well as European traders who valued it highly (15).

- Squash and Pumpkins: Key crops in their agricultural repertoire, traded locally (15).

- Cotton: Grown by the Tupi for making textiles and to be traded for other goods (15).

Other Agricultural Products

- Fish, Game, Meat: Surplus fish from rivers and game meat from hunting were commonly traded among tribes, enhancing dietary diversity and food security.

- Handicrafts: Including pottery, woven baskets, and tools were also traded locally.

CITATIONS

- The History of Brazil – From the Indigenous People to Independence

- History of Brazil – Colonialism, Independence

- Indigenous Peoples in Brazil

- Agriculture in Brazil

- Brazilian Indigenous Peoples

- Portugese Brazil – World History Encyclopedia

- Indigenous Surui

- The Uprooting of Indigenous Women’s Horticultural Practices in Brazil – Oxford Academic

- The consumption of meat in Brazil: between socio-cultural and nutritional values

- Brazilian Cuisine

- Indigenous Agriculture at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century

- Indigenous Participation in the Native Seed Market

- Indigenous-Led Seed Bank Protects the Amazon’s Biodiversity

- The Brazilwood Trade from the Mid-Sixteenth to Mid-Seventeenth Century

- Exploring food sovereignty among Amazonian peoples

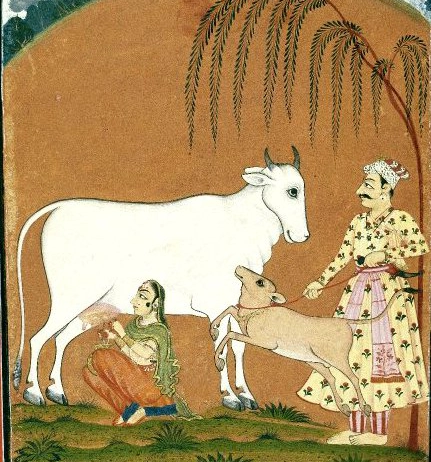

India

Indigenous name: Bhārat or Sindhu

Indigenous peoples: Adivasi peoples

en

What is the indigenous name of that country?

Who were the original peoples of the land?

How far back can we see the agriculture of this land?

The Neolithic Revolution, or First Agricultural Revolution, in India is believed to have begun around 8000-4000 BCE, marked by the earliest evidence of wild rice, wheat, and barley cultivation, as well as animal domestication in Northern India (3)(4)(5).

What tools did they use?

- Plows: Wooden plows drawn by oxen were a primary implement for tillage (6, 7).

- Sickles: Small hand sickles used for harvesting crops like wheat, barley, pulses, and grass (8).

Levelers and Clod Crushers: Rectangular wooden beams drawn by bullocks, used to smooth the soil surface before sowing (6). - Kodali: An iron blade fitted to a wooden handle, used as a hand tool for digging and weeding (6).

- Seed drills: Bamboo tubes attached to plows,used for sowing seeds (6).

- Threshing tools: Wooden poles or mallets used to thresh grains by beating (8).

- Winnowing tools: Sieves made of grass stalks or bamboo,used to separate grain from chaff (6).

Spades (Pharwa) and Hoes (Kudali): Used for digging and weeding operations (8). - Axes (Kulhari): Used for harvesting crops like sugarcane (8).

- Stone Tools: Used in very early periods before the widespread adoption of medal tools (9).

What animals did they manage?

What resources did they have available?

- Land and Soil: Fertile plains, especially along river valleys like the Indus and Ganges, with various soil types suitable for different crops, classified into categories like urvara (fertile), ushara (barren), and maru (desert).

- Water Resources: Rivers, monsoon rains, and irrigation systems, including wells, canals, and tanks (11).

- Crop diversity: A wide range of crops cultivated, including cotton for textiles, spices, and medicinal plants.

- Farming Practices: Use of organic fertilizers like cow dung, ash, and compost; traditional knowledge of crop rotation, plowing, fallowing, and regenerative farming methods.

- Climate Understanding: Knowledge of seasonal and climate patterns to guide agricultural activities.

Tools: Use of plows (initially wooden, later iron) and sickles (1) (15).

What were the staple crops?

- Barley, rice, cotton, and sesame (6).

- Wheat: einkorn, emmer, durum, and bread wheat (6).

- Legumes: mung beans, black gram, horsegram, and pigeon pea, field peas, and lentils (6).

The cultivation of these crops marked the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agricultural communities in the Indian subcontinent.

What foods did they eat?

- The indigenous diet was characterized by its reliance on locally sourced ingredients, reflecting a deep connection to the land and nature. It varied across different regions based on local ecosystems and available resources (14) (12) (13).

- A traditional diet consisted mainly of meat, rice, wild game, seasonal vegetables, forest fruits, fish and insects. Cooking methods such as fermenting, sun-drying,pickling, smoking, drying, and roasting were commonly used. Ingredients were minimal, typically limited to salt, turmeric, chili, onion, and garlic (13).

- Examples of common foods include rice, millets, maize, pork, field rats, chicken, fish, wild game, fermented raw milk, snails, red ants (for chutney), wild fruits and berries (bael), seasonal vegetables (sabzi), bamboo shoots, tubers, and roots (14)(12)(13).

What did they trade and who did they trade with?

Trade between indigenous groups in India predates European contact. Different tribes exchanged goods across ecological zones, often trading items from different altitudes or regions (2). The original indigenous peoples of India traded several agricultural resources:

- Crops: Kidney beans, potatoes, garlic, maize and rice (traded for by communities unable to grow them locally).

- Processed foods: Finger millet flour, honey, clarified butter (ghee).

- Spices

- Cotton: Used for textiles.

Other Agricultural Products

- Milk products, Dried and Pickled Foods: Examples include dried radish, taro roots, gourds, fenugreek leaves, pickled garlic and chillies.

- Dried Meat: Primarily sheep and goats.

Trading Partners:

- Personalized Trade Networks: Trade was highly personalized, with groups establishing long-term relationships, sometimes through fictive kinship ties, to ensure reliable access to goods from other regions year after year (19).

- Trade Between Indigenous Groups: Highland communities with pack animals (like llamas) traded with lowland agricultural communities, exchanging goods from different ecological zones (19).

- Early Maritime Trade: Coastal indigenous groups engaged in maritime trade, with evidence of trade connections to Babylon and other ancient civilizations (20).

- Response to European Contact: Many indigenous groups adapted their existing trade networks to engage in new forms of commerce, particularly in the fur trade, after European arrival (21).

Cultural exchange: Trade facilitated not only the exchange of goods but also the sharing of ideas, technologies, and cultural practices between different indigenous groups and later with non-indigenous traders (22).

CITATIONS

- Adivasi

- India, Largely a Country of Immigrants

- History of Agriculture in India

- History of agriculture in the Indian subcontinent

- History of Indian Agriculture

- The Indian Sub-Continent: Origins of Agriculture

- Tools of Agriculture in the Indus Civilization

- Tools and Instruments – Chapter 9

- Traditional Agricultural Tools

- Agriculture: Vedic Heritage

- Agriculture in India

- Politics of the Plate: An account of Adivasi Culinary Aesthetic

- Exploring the Traditional Foodways for Nutritional Wellbeing

- Indigenous Foods of India

- Agri – Kaleidoscope: Agricultural Heritage

- Research in Agricultural and Applied Economics

- Agriculture Trade Policy

- Trade and Agriculture – India’s Perspective

- Indian Trade and Ethnic Economies

- Contact with the West

- Indian commerce with early English colonists and the early United States

- Ancient India Trade Routes

Senegal

Indigenous name: “Senegal” is not an indigenous name but has roots in the cultures of the region. The name “Senegal” is believed to derive from the Senegal River, which forms the northern border of the country. The original names used by indigenous peoples for their territories varied depending on the specific group.

Indigenous peoples: Wolof, Serer, Fulal, Jola, Sonimke and Mandika Peoples

en

What is the indigenous name of that country?

Who were the original peoples of the land?

The area now known as Senegal was home to various kingdoms and empires, each with their own names. For example, The Jolof Empire, founded in the 13th-14th centuries, covered much of present-day Senegal (1). The Kingdom of Tekrur (or Takrur) existed in the area from around the 9th century (2).

How far back can we see the agriculture of this land?

- Neolithic Era: Agriculture began in Senegal during the Neolithic period, around 3000 BCE, marking the domestication of plants and animals (3).

- Iron Age: Around 1000 BCE, agricultural techniques became more advanced, with communities practicing mixed farming and engaging in trade. The introduction of iron tools significantly improved farming efficiency (4).

- Medieval Period: From the 8th century onward, agriculture was further developed alongside the rise of significant empires in West Africa, such as the Ghana and Mali Empires (5).

- Islamic Influence: The arrival of Islam in the region around the 11th century brought new agricultural practices and crop varieties (3)(6).

What tools did they use?

- Hand Hoes: Used for tilling, weeding, and planting (14).

Animal-Drawn Plows and Cultivators: Used in agriculture and pulled by oxen or donkeys. - Sickles: Used for harvesting crops

- Carts: Pulled by animals and used for transporting goods and produce from fields to markets or storage areas (13).

- Mortars and Pestles: Used for processing grains and seeds

What animals did they manage?

What resources did they have available?

- Arable Land: Approximately 75% of the population engaged in agricultural activities (14).

- Water Resources: The Senegal River, along with the Gambia and Casamance Rivers, provided essential water sources for irrigation and fishing.

- Forests: Offer timber and fuelwood, with baobab trees being particularly important for their fruit and wood (15).

- Crops: Staple crops cultivated by indigenous peoples include millet, sorghum, rice, groundnuts (peanuts), maize (corn), cassava, and beans.

- Fisheries: Rich coastal waters abundant in fish species such as tuna, sardines, and shrimp make fishing a major economic activity and a vital protein source for the population (14).

- Livestock: Indigenous peoples managed various livestock, including cattle, goats, sheep, and poultry,providing meat, milk, labor for farming, and other essential resources.

What were the staple crops?

Staple crops: Millet, sorghum, maize, rice, cassava, peanuts, cowpea (1)(6)(7)(8).

What foods did they eat?

- A traditional diet in Senegal consisted mainly of millet and sorghum, broken rice (Riz Brisé), seasonal vegetables, fish and tropical fruits. A variety of cooking methods were also used, such as fermenting, soaking of all grain, stewing, and cooking over open fire.

- Specific examples of foods include millet, sorghum, fermented cassava (Attiéke), fish, chicken, okra, eggplant, mangoes, bananas, boab.

- Cultural eating traditions include communal eating, where meals are typically served from a communal bowl and family members share food using their right hands, fostering togetherness (16) (17) (18) (19).

What did they trade and who did they trade with?

The indigenous peoples of Senegal were integral to broader West African and trans-Saharan trade systems long before Europeans arrived. The Wolof people, one of Senegal’s major ethnic groups, were “known throughout the region for their robust trade economy” (24). There were extensive “long-range trade” networks within Africa that connected various peoples and regions (23).

The indigenous peoples of Senegal traded several agricultural and natural resources including:

- Fish: Seafood such as fish, and shrimp (20).

- Soups and broths (20).

Other Products

Trading Partners:

Prior to the European voyages of exploration in the fifteenth century, African rulers and merchants had established trade links with the Mediterranean world, Western Asia, and the Indian Ocean region. Within the continent itself, local exchanges among adjacent peoples fit into a greater framework of long-range trade (23).

CITATIONS

- Senegal

- History of Senegal – Brittania

- Agriculture in Senegal

- Agricultural Crisis

- Economy of Senegal

- Climate-Smart Agriculture Country Profile

- Senegal – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- Agricultural Distortions Working Paper

- A Typology of Production Systems: Senegal

- AICCRA – Climate Research for Africa

- Livestock Farming in West Africa: Senegal

- Farm Power in Senegal

- Farm Equipment in Senegal

- The Major Natural Resources of Senegal

- Senegal – Culture, History, and People

- Top 10 Traditional Foods of Senegal

- Customs and Cuisines of Senegal

- Senegalese Cuisine

- Senegalese Food: Traditional Dishes

- Senegal – Export Diversification

- Senegal – East Analytics

- Senegal Trade

- Trade Relations among European and African Nations

- Senegal Ethnic Cultural Field Guide

Santa Barbara

The original indigenous name of Santa Barbara is Syuxtun and the original peoples are the Chumash peoples, settling over 5,000 years ago. They call the broader region Siujitu and were caretakers of the western gateway of the Pacific.

Several Chumash villages flourished in what is now Santa Barbara:

- Syuxtun: The largest village, located between Bath and Chapala streets

- Mispu: Now occupied by Santa Barbara City College

- Amolomol: At the mouth of Mission Creek

- Swetete: Above the present bird refuge

en

What is the indigenous name of that country?

Who were the original peoples of the land?

The Chumash people were the original inhabitants of the Santa Barbara region, having settled there more than 5,000 years ago (3). They called the broader region Siujitu and believed they were caretakers of the western gateway of the Pacific (3). Several Chumash villages flourished in what is now Santa Barbara:

- Syuxtun: The largest village, located between Bath and Chapala streets

- Mispu: Now occupied by Santa Barbara City College

- Amolomol: At the mouth of Mission Creek

- Swetete: Above the present bird refuge

We can trace the Chumash people back approximately 13,000 to 15,000 years in the coastal regions of southern California.

How far back can we see the agriculture of this land?

The Chumash people have a long history of plant management and food production practices that evolved over thousands of years. While they did not practice agriculture in the modern sense, their sophisticated approach to plant use can be traced back approximately 8,500 years:

- Early Plant Use: During the “Millingstone Horizon” or “Oak Grove” period, the Chumash began using milling stones (basin metates and manos) to grind small, hard seeds from grasses and sage (4). This marks the earliest evidence of plant-based food processing in the region.

- Intensification of Plant Management: Around 5,000 years ago, stone mortars and pestles appeared, indicating that acorns had become an important food source (4). By 3,200 years ago, the Chumash were practicing more sophisticated plant management, including selective burning to promote the growth of seed-bearing plants (4).

- Impact of European Contact: The arrival of Spanish colonizers in the late 18th century brought significant changes to the Chumash landscape and traditional food systems (5). The missions and ranchos introduced large herds of cattle, horses, and sheep, which devoured much of the native vegetation (5).

What tools did they use?

- Grinding Implements: Mortars, pestles, metates, and manos were used for grinding seeds, nuts, and acorns (6)(7).

- Stone Tools: Knives, saws, scrapers, chisels, axes, hammer-stones, and drills were made from flaked stone (6).

- Wooden Tools: Many tools were made from wood and fitted with wooden handles (6).

- Antler Tools: Antler wedges were used to split logs (8).

- Shell Tools: Rubbing tools made of shell were used for smoothing wooden planks (8).

- Baskets: The Chumash were skilled basket weavers, creating a variety of baskets for different purposes, including storage and food preparation (7).

- Plank Boats (tomols): These were built from driftwood, preferably redwood, sewn together with plant fibers and sealed with moss and asphaltum (6).

- Fishing Equipment: Fishing lines were made from dogbane (7).

- Cooking Implements: Waterproof cooking baskets lined with tar were created (6).

- Hunting Tools: Bows, arrows, and spears were used for hunting.

What animals did they manage?

What resources did they have available?

- Seafood and Marine Resources: The Chumash homeland was rich in marine life, providing a wide variety of food supplies. They relied heavily on the sea, using over a hundred kinds of fish and gathering shellfish such as clams, mussels, and abalone (9).

- Land Animals: They hunted both small and large animals, including deer, rabbits, bear, and quail (9).

- Plant Foods: The Chumash gathered acorns, a staple food, as well as over 150 species of wild native plants for food, medicine, clothing, shelter, basketry, and tools (9).

- Vegetation for Tools and Shelter: Materials like juncus rush and tule (bulrush) were used for basketry and building shelters. Driftwood, especially redwood, was used to build plank boats (tomols) (9).

- Medicinal Plants: The Chumash utilized various plants for medicinal purposes. For example, willow bark was used for its medicinal properties (6).

- Water Resources: The Chumash had access to freshwater sources such as rivers and creeks. Today, the Santa Ynez Chumash Environmental Office monitors water quality in Zanja de Cota Creek to ensure ecosystem health (6).

- Raw Materials for Trade: Shells were used to make bead money (‘alchum) and traded obsidian (volcanic glass) obtained through their extensive trade networks (9).

These resources supported a complex society with a rich cultural heritage that was deeply connected to the natural environment around them.

What were the staple crops?

The Chumash did not cultivate crops in the traditional agricultural sense. Their primary staple foods were gathered from the wild rather than grown. The Chumash relied on a variety of plant foods, including:

- Acorns: A staple food, gathered in fall and processed to remove tannins (4).

- Seeds: Manzanita, chia, and others were ground into meals (4).

- Bulbs, Roots, and Tubers: Roasted or baked in underground earth ovens (4).

Rather than cultivating crops, the Chumash practiced sophisticated plant management:

- Selective burning to promote desired plant growth (4).

- Gathering expeditions to mainland areas for plants less abundant on the islands (5).

What foods did they eat?

- A traditional diet in Senegal consisted mainly of millet and sorghum, broken rice (Riz Brisé), seasonal vegetables, fish and tropical fruits. A variety of cooking methods were also used, such as fermenting, soaking of all grain, stewing, and cooking over open fire.

- Specific examples of foods include millet, sorghum, fermented cassava (Attiéke), fish, chicken, okra, eggplant, mangoes, bananas, boab.

- Cultural eating traditions include communal eating, where meals are typically served from a communal bowl and family members share food using their right hands, fostering togetherness (16) (17) (18) (19).

What did they trade and who did they trade with?

The Chumash people engaged in extensive trade with various tribes both along the coast and inland. They had well-established trade networks that facilitated the exchange of goods over long distances, helping maintain social connections and alliances with neighboring tribes. This contributed to regional cohesion and stability (11).

The indigenous Chumash peoples traded several agricultural and natural resources including:

- Marine Resources: Items from the sea, such as abalone, clams, and shell beads (11).

- Crafted Goods: The Chumash were known for their finely crafted baskets and wooden boats (tomols), which were also traded (11).

- Food Items: Plant foods like acorns and seeds were traded for their importance in ritual offerings (12).

- Raw Materials: Obsidian, salt, and black pigment (11).

Trading Partners:

- Yokuts: The Chumash traded marine resources with the Yokuts of the Central Valley in exchange for goods like obsidian and antelope skins (11).

- Salinans: They supplied the Salinans in the north with wooden boats and beads (11).

- Mojave Indians: The Chumash traded with the Mojave Indians, who lived over 400 miles away (11).

CITATIONS

- A History of Santa Barbara

- History of Santa Barbara

- Indigenous People: Chumash Indians

- Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History: Timeline

- Chumash Native Plant Usage

- Chumash Era

- Chumash – Kids: Brittania

- What did the Chumash use for Tools?

- Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History: Daily Life

- What did the Chumash Eat?

- Native Americans of the Californian Coast: The Chumash

- Sukinanik’oy Garden of Chumash Plants

Immersive Experiences: From Soul to Soil

Experience living traditions from around the world and remember your innate connection to Earth, self, and story—past, present, and future.

en

This multi-sensory event invited attendees to step beyond data and into embodied connection through culture, community, and the land that sustains us. Through each space, participants were guided not only to remember where they come from, but to reimagine where we might go.

Who are We?

“Always” – The Biome

Where do we come from?

“Yesterday” – Ancestral Bloodlines

Where are we?

“Today” – The State of the Soil

How Do we want to proceed?

“Tomorrow” – A New Ancient Emerging

What is the role of agriculture in shaping our future?

From Soul to Soil was inspired by the belief that “Every tomorrow emerges from culture.” The evening honored Indigenous wisdom from Angola, India, Senegal, Brazil, and beyond, weaving together the past, present, and future into one shared moment of reverence and reconnection.

Together, we rekindled the bond between culture and agriculture—through story, scent, ceremony, and song. And together, we asked what it means to be truly human in this era of planetary transformation.

From Soul to Soil—an evening where storytelling, science, and spirit converged in celebration of Earth, ancestry, and the path ahead.

Watch the Video Below to Immerse Yourself in Living Traditions from Around the World

Why Stories

From Náhuatl “Nanathli”: “mother”, “grandmother”, “womb”, “the one that nurtures”, NANA is a multi-media experiential platform where ancient whispers intertwine with modern echoes in a symphony of flavors, wisdom, and traditions. Here, we invite you to journey with us back to the heart of heritage, with food as a bridge between past, present, and future.

NANA invites you to immerse yourself in the rich tapestry of ancestral paradigms as we honor the wisdom of our Elders who, with their knowledge, weave together the threads of our ancient and modern worlds.

Read More about farmer’s footprint’s mission

Why Stories

From Náhuatl “Nanathli”: “mother”, “grandmother”, “womb”, “the one that nurtures”, NANA is a multi-media experiential platform where ancient whispers intertwine with modern echoes in a symphony of flavors, wisdom, and traditions. Here, we invite you to journey with us back to the heart of heritage, with food as a bridge between past, present, and future.

NANA invites you to immerse yourself in the rich tapestry of ancestral paradigms as we honor the wisdom of our Elders who, with their knowledge, weave together the threads of our ancient and modern worlds.

As we gather around rich culinary experiences, curious kitchen conversations, and intimate community gatherings, NANA reawakens the sacred bonds that connect us to ancestral wisdom.

Read More about farmer’s footprint’s mission

RECONNECTING WITH OUR INDIGENEITY: We Are All Ancestral

NATIVE AMERICAN ELDERS OF CHUMASH

The Story of Our Return to Culture through Land, Food, and Story.

ANCESTRAL FOODS: CACAO

The origin, medicine, and a call to liberation

FROM SOUL TO SOIL: An Immersive Event

Experience living traditions from around the world and remember your innate connection to Earth, self, and story—past, present, and future.

THE CHINAMPAS OF XOCHIMILCO

Portals to Ancestral Wisdom: Women, Soil, and the Spirit of Xochimilco

SANTA BARBARA

Indigenous name: Syuxtun

Indigenous peoples: Chumash

Sit with Elders

Ancient Teachings for a Modern World

Sit With Elders is a storytelling series sharing conversations with Indigenous elders from around the world. Their voices offer guidance on how to live in right relationship—with the land, our food, and one another. These stories carry practical wisdom: how food was grown and shared, how communities cared for each other, and how life was lived with reverence. They show us that science and spirit can walk together.

Through their teachings, we’re invited to reconnect—with the earth, with ancestral knowledge, and with the hope of healing, for ourselves and for future generations.

RECONNECTING WITH OUR INDIGENEITY: We Are All Ancestral

NATIVE AMERICAN ELDERS OF CHUMASH

The Story of Our Return to Culture through Land, Food, and Story.

THE VITAL ROLE OF ELDERS

PERUVIAN ELDERS OF QERO’S

There has never been a more important time in history to listen when our elders speak.

BRIDGING SCIENCE AND SPIRIT

Colombian Elders of the Arhuaco & Wiwa

Coming Soon

RESTORING NATURAL BALANCE TO THE EARTH AND COMMUNITY

AMAZONIAN ELDERS OF Tapajós

Coming Soon

LOCAL FOOD SYSTEMS AND LOCAL COMMUNITIES

Indian Elders of the ladakh nation

Coming Soon

Ancestral Foods

A Return to Wisdom

Ancestral Foods is a homecoming—a return to what has always nourished us. In a world of trends, this series explores foods rooted in land, culture, and community. These are the local, seasonal staples that sustained generations—prepared with care and meaning.

More than fuel, food is language, ritual, and relationship. We ask: What grows where I live? What did my ancestors eat—and why? How can traditions like fermentation and foraging guide us toward deeper nourishment?

This series is not about going backward, but reaching inward—drawing on ancestral wisdom to shape a rooted, place-based food future.

When we eat with reverence, we remember who we are.

CACAO

THE ORIGIN, MEDICINE, AND A CALL TO LIBERATION

HERITAGE SEEDS OF LIFE

SEED STORIES

Coming Soon

HERITAGE CORN AND THE STORY OF MEXICO

THE FOUNDATIONS OF CULTURE

Coming Soon

DO YOU HAVE A STORY THAT YOU WANT TO SHARE?

Do you have a story that you want to share with us that resonates with our Ancestral Foods Series? If so, get in touch: [email protected]

Culture in Agriculture

“We can’t meaningfully proceed with healing, with restoration, without “re-story-ation.”

– Robin Wall Kimmerer, citing Gary Nabhan in Braiding Sweetgrass

Culture in Agriculture is a storytelling series rooted in the belief that healing the land begins with remembering. Inspired by re-story-ation, it shares stories of farmers, seed keepers, and culture bearers who walk in ancestral ways. Regenerative agriculture is a return to traditional food systems and relationships that have long sustained life. These stories remind us that agriculture is more than food—it’s reciprocity, ceremony, and belonging. The health of soil and people are one.

By re-story-ing the land, we begin to restore it.

THE CHINAMPAS OF XOCHIMILCO

Portals to Ancestral Wisdom: Women, Soil, and the Spirit of Xochimilco

HOPI AGRICULTURAL WISDOM

HOW THE HOPI PEOPLE OF NATIVE AMERICA HAVE HANDED DOWN INTERGENERATIONAL WISDOWM TO FARM IN THE DESERT

Coming Soon

THE PROFOUND INTELLIGENCE OF LIFE’S NATURAL CYCLES

AGRO-ECOLOGY IN SOUTH AFRICA WITH RATANANG COLAB

Coming Soon

DO YOU HAVE A STORY THAT YOU WANT TO SHARE?

Do you have a story that you want to share with us that resonates with our Culture in Agriculture Series? If so, get in touch: [email protected]

Immersive Experiences

Culture, Community, and Celebration

At NANA, we believe true connection doesn’t come from information alone—it comes from experience. In a world of data, we return to the body’s deeper intelligence: intuition, memory, imagination. Our immersive gatherings awaken the senses through rhythm, texture, sound, and story.

The medium is the message.

We begin with play and conversation, engaging in the timeless ritual of coming together. These spaces invite participation, not just observation—inviting us to co-create, celebrate, and belong.

Each experience is a living mosaic of people and practices. Here, we show up as we are and weave our stories into the fabric of community.

FROM SOUL TO SOIL

Experience living traditions from around the world and remember your innate connection to Earth, self, and story—past, present, and future.

A BLEND OF TRADITION AND MEMORIES

AN INTIMATE MEAL STEEPED IN LOVE

Coming Soon

MEXIPPON

THE UNITY OF MEXICAN AND JAPANESE FOOD CULTURE

Coming Soon

DO YOU HAVE A STORY THAT YOU WANT TO SHARE?

Do you have a story that you want to share with us that resonates with our Immersive Experiences Series? If so, get in touch: [email protected]

ORIGIN STORIES

Restoring reverence to the origin through listening to the stories held by the land and its First Peoples.

To look ahead, we must first look back — to origin. Origin Stories is a series that honours ancestral connections between people and place. Each feature released by Farmer’s Footprint is paired with a companion story — one that roots us in the original foodways of the land and its First Peoples. These stories illuminate how food was once honored, culture interwoven with land care, and reciprocity central to life. Guided by First Nations wisdom, this series invites us to slow down, listen deeply, and ask: What grew here, and how was it tended? It’s a call to restore reverence — for origin, for relationship, and for the living legacies still guiding us home.

ANGOLA

Indigenous name: no singular unified name as various indigenous groups inhabited the land before the Portuguese named it ‘Angola’

Indigenous peoples: Saan + Khoisan + Bantu Peoples

BRAZIL

Indigenous name: The land was inhabited by over 2000 indigenous groups with their own territories and names.

Indigenous peoples: Tupi + Tapuia (Jê) + Caribs + Nuaraque peoples

INDIA

Indigenous name: Bhārat or Sindhu

Indigenous peoples: Adivasi peoples

SENEGAL

Indigenous name: “Senegal” is not an indigenous name but has roots in the cultures of the region. The name “Senegal” is believed to derive from the Senegal River, which forms the northern border of the country.

SANTA BARBARA

Indigenous name: Syuxtun

Indigenous peoples: Chumash

Enter your email to stay in the know. Get recipes and stories directly to your inbox.

A journey back to intuitive, seasonal cooking—where meals are guided by love, memory, and what’s at hand, transforming food into a story, a ritual, and a way home.

In every dish we make, there are stories. Fragments of memory, ancestral echoes, whispers of places we’ve known — or longed for. Recipes handed down or simply felt, not written. Meals that nourished not just the body, but the spirit.

In the Kitchen with NANA is a series that brings us back to that place. A place where cooking is less about precision, and more about presence. Less about instruction, and more about intuition. Here, we invite you to begin not with a list of ingredients, but with what’s before you — what’s in season, what’s leftover, what’s growing near you, what’s been gifted, gathered, or simply waiting to be seen.

Our NANA’s cooked this way. Guided by love. By necessity. By quiet knowing. They cooked with what they had and with who they were feeding in mind — bringing nourishment into the world with a kind of grace that didn’t require measurement or mastery.

This series is an offering: to reawaken your senses, trust your instincts, and enter the kitchen as a place of communion. To deepen your connection to food and culture through the everyday act of preparing a meal. To let memory, intuition, and curiosity guide your hands.Let cooking become a conversation — with the land, with the people who came before, and with the ones you’ll gather around your table today. Let it be an act of care. A ritual of restoration.

Because food, when prepared with intention, is never just food. It’s lineage. It’s culture. It’s a way home.

Hemp Pesto

INGREDIENTS

A bunch of kale

Two cloves of garlic

A palm-ful of hemp seeds

A lug of good olive oil

A pinch of salt

PREPARATION

Dark and leafy kale forms the hearty base of this pesto, bringing a robust earthiness to the dish. Hemp seeds, which are rich in protein and omega-3s, replace the traditional pine nuts, adding an earthy, almost buttery flavor that’s perfectly complemented by the warmth of fresh garlic.

As you blend everything together with a generous drizzle of olive oil and a sprinkle of salt, the ingredients transform into a vibrant, green paste that’s as versatile as it is flavorful. Toss it with pasta, spread it on toast, or use it as a dip—this Hemp Pesto is a celebration of nourishment and creativity in the kitchen.

Every spoonful is a reminder that healthy eating doesn’t have to be complicated. With simple, whole ingredients, you can create something that’s not only nourishing but also deeply satisfying and delicious.

Whole Roasted Chicken with Mustard & Orange

INGREDIENTS

1 whole chicken (ideally organic or pasture-raised)

3–4 onions, sliced into thick rounds

4–5 garlic cloves, smashed

4–5 small potatoes, chopped into chunks

A generous amount of mustard — Dijon or regular (enough to coat the bird)

Juice of 3–4 oranges

A few sprigs of fresh rosemary and thyme

Olive oil

Salt and pepper

PREPARATION

Prepare Your Nest.

Lay the onion slices in the bottom of your pot — this will be the chicken’s resting bed and will soak up all the flavor.

Dress the Bird.

Rub the whole chicken inside and out with mustard — don’t be shy. You want it slathered like a proper marinade. Drizzle with olive oil, season with salt and pepper, and tuck a few garlic cloves and herbs inside the cavity if you like.

Add the Goodness.

Scatter the chopped potatoes and smashed garlic around the chicken. Pour the fresh orange juice over everything. Tuck in your rosemary and thyme.

Cover and Roast.

Cover your pot (or seal tightly with foil if you’re improvising) and place in a preheated oven at 350°F (175°C). Let it roast low and slow for about 2.5–3 hours. The citrus will tenderize the meat and infuse it with deep, fragrant flavor.

Uncover & Crisp (Optional).

In the last 20 minutes, uncover the chicken to let the skin crisp up a bit. The juices will caramelize beautifully.

Rest & Serve.

Let the chicken rest before carving. Serve with the tender onions, potatoes, and a spoonful of the pan juices.

A Final Note:

This is more than a meal — it’s a memory waiting to happen. One of those recipes that turns a quiet night into something a little more special. And when you’re done? Don’t forget to save the bones. That’s tomorrow’s broth — and another kind of nourishment altogether.

Fresh Greek Salad

INGREDIENTS

Half a red onion

One bell pepper

A cucumber

A handful of cherry tomatoes

Fresh mint, to your liking

A few ounces of marinated feta

A handful of kalamata olives (pitted!)

For the Vinaigrette:

A dash of Dijon mustard

A clove of garlic

Two parts olive oil

One part balsamic vinegar

Honey to taste

PREPARATION

To make the salad, simply chop the ingredients into bite sized pieces and toss together. The vinaigrette comes together easily in a small bowl or jar, the delicious blend of Dijon mustard, balsamic vinegar, and honey tying together the bold flavours of the raw ingredients with a touch of sweetness and tang.

*A tip from Barbra Rigelhof: crush the clove of garlic with a pinch of salt in a mortar and pestle until it almost liquefies, making it the perfect base for this luscious dressing.

Each bite of this Greek salad transports you to a place where time slows down, and the simple pleasures of life—good food, good company, and a beautiful view—take center stage.

Pan Fried Stuffed Squash Blossoms

INGREDIENTS

Half a dozen Squash blossoms

A cup of Ricotta

A handful of curly parsley

Two or three stems of green onions

One or two garlic cloves

PREPARATION

Gently fill each blossom with the creamy mixture of ricotta, curly parsley, and green onions, all lightly kissed by the warmth of fresh garlic. The stuffing is rich yet light, a perfect complement to the tender blossoms that encase it. Heat up the pan and drizzle a little bit of your cooking oil of preference. Gently place the stuffed blossoms on the pan until the edges start to get golden, then carefully flip them to the other side and do the same. The blossoms should look like pan-fried gyozas, a little crispy on the outside but not too cooked. This will enhance the flavors of the ingredients and bring out a unique flavor in the blossom itself.

As you take that first bite, the blossoms yield to the savory filling, with each flavor unfolding on your tongue in a delicate dance. The ricotta is smooth and mild, allowing the herbs and garlic to shine through. This dish is a fleeting pleasure, much like the short season of the squash blossoms themselves—a gentle reminder to savor the beauty of the present moment.

Stuffed squash blossoms embody the art of simple, seasonal cooking, where the ingredients speak for themselves and every meal becomes an experience to cherish.

Summer Calabacita Tacos

INGREDIENTS

Half an onion, your choice of color

One or two cloves of garlic

A large ear of corn

Two summer squashes

Two tomatoes

An avocado, sliced

Condiments: olive oil, salt, pepper, herbs of your choice.

+ Salsa of your choice

The Corn Tortillas

1 cup Nixtamalized corn flour

1 cup water

Pinch or two of salt

PREPARATION

Begin by heating a large pan over medium heat and adding a generous splash of olive oil. Caramelize the onion until it turns translucent and aromatic. While the onion cooks, chop your squash into bite-sized pieces, by the time you finish you can add this to the pan with the garlic. At this point, a pinch of salt will help encourage the vegetables to transform.

Next, cut the raw corn kernels from the cob and add them to the pan. Follow with the tomatoes, adding them last due to their delicate texture. Allow the tomatoes to warm through and the flavors to meld, reducing the heat while you prepare the tortillas.

In Mexico, where I was born and raised, we hold that the tortilla is the heart of a good taco. A subpar tortilla can undermine even the best filling. Making tortillas from scratch is simple and will give you a much more delicious vessel than the ones at the store.. My preferred masa, or corn flour, undergoes the traditional Nixtamalization process, which has been used in Mexico for many generations. The corn is mixed with lime, triggering fermentation which enriches the tortillas with prebiotic and probiotic properties, making them both nutritious and delicious.

To make the tortillas, mix corn flour, water, and a pinch of salt in a bowl until a dough forms. If you don’t have a tortilla press, not to worry – shape golf-ball-sized portions of dough by hand. Place each ball between two sheets of baking paper and flatten with either your press or two heavy books until they are circular, round and flat. Cook each tortilla in a hot, dry pan for a few moments on each side until slightly puffed.

Now you can assemble your tacos. Add the warm, vegetable filling to the tortilla.

A few slices of creamy avocado and a sprinkle of herbs add the perfect finishing touch. These tacos are more than just a meal; they’re a connection to the land, a reminder of the deep-rooted knowledge passed down through generations. Each bite is a celebration of resilience, community, and the enduring power of ancestral wisdom.

I’ll leave you with an old saying in Mexican culture that resonated deeply with me when I first heard it ‘As long as the people take care of the corn, the corn will take care of the people’.

Bone Broth — A Gut-Healing Ritual

INGREDIENTS

Leftover bones or a fresh chicken carcass — from a whole chicken you’ve roasted, a Sunday soup, or anything you’ve cooked “nose to tail”; or a fresh chicken carcass from your local butcher

Vegetable scraps — think celery stalks, carrot ends, onion skins, garlic bits

Healing roots — fresh ginger, turmeric (a thumb-sized piece of each)

Aromatics — a stalk of lemongrass, bruised to release its citrusy oils

A splash of apple cider vinegar — to help draw out minerals from the bones

Optional: bay leaves, black peppercorns, herbs past their prime (like parsley or thyme)

PREPARATION

Save as You Go.

Throughout the week, tuck veggie scraps and bones into a freezer bag or container in your fridge. When it’s full, you’re ready.

If you don’t have any veggie scraps – add two to three carrots, an onion, garlic and half a celery.

Fill the Pot.

Add your bones and scraps to a big stockpot, slow cooker, or pressure cooker. Cover with cold water, leaving a few inches of space at the top.

Add the Good Stuff.

Drop in your ginger, turmeric, lemongrass, and vinegar. Add bay leaves or herbs if you’ve got them lying around.

Simmer or Pressure Cook.

Traditional: Bring to a boil, then lower to a gentle simmer. Skim any foam. Let it cook low and slow — anywhere from 8 to 24 hours.

Pressure Cooker: Short on time? Use a pressure cooker and simmer under pressure for 4-6 hours. It speeds up the process without sacrificing depth.

Cool & Store.

Let it cool fully before straining. Pour into jars or containers. In the fridge, you’ll know you’ve done it right when it turns gelatinous — that’s the collagen and minerals doing their healing work.

Sip it warm with a pinch of sea salt and a squeeze of lemon. Drink it first thing in the morning or in the quiet of the evening — like a grounding ritual. It also makes a beautiful base for soups, stews, grains, or to gently sauté greens.

Why It Matters:

Bone broth is full of collagen, minerals, and anti-inflammatory compounds. It supports your gut lining, strengthens your immune system, and nourishes you at the cellular level. This is ancestral nourishment — slow, intentional, and deeply healing.

Andalusian Gazpacho: A Taste of Summer’s Abundance

INGREDIENTS

5 very ripe tomatoes

½ bell pepper

½ cucumber (peeled and seeded)

¼ white onion

1-2 garlic cloves

2 tbsp sherry or red wine vinegar

4 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

1 slice stale bread (optional, for extra body)

Cold water (as needed, to reach desired consistency)

Salt and pepper to taste

To Serve: