MEET A FARMER

GAIL FULLER

Circle 7 Farm

Severy, Kansas

“I just couldn’t imagine it,” Fuller, now 58, says, “As a young kid living close to a river, how the hell can a river burn? Rivers are made of water.”

The historic event ended up in the annals of U.S. history, a lightning rod for the emerging environmental movement of the early 1970s. For Fuller, a 3rd generation Kansas farm kid, it was a singular life impression. An experience that would merge with many more to shape the farmer, partner and man he is today, fueling his passion for regenerative agriculture and rebuilding farm communities.

The Cuyahoga River Fire meant something to six-year-old Fuller, even if he wasn’t quite sure what that was, at the time. The fire wasn’t the moment that pushed him toward his regenerative journey, it was one of many.

“It was like a blizzard,” Fuller says, when asked what convinced him to switch from a monoculture, commodity crop farmer to using diversified, regenerative practices and committed to regenerative agriculture as a catalyst for rebuilding rural communities.

Growing Up on a Kansas Family Farm

His childhood farm was a typical Kansas farm. They had six crops in rotation — corn, wheat, grain sorghum, alfalfa, sorghum silage and soybeans — a few cattle, a lot of hogs and chickens for family eating. Two households lived on the property, Fuller’s parents and his brother in one farmhouse, his grandparents nearby in another. They had three large gardens between them and grew and canned most of their food. Their farm was diverse and, for all intents and purposes, organic — simply because nobody spent money or fertilizers or chemicals back then, Fuller recalls.

I can still remember Dad buying some fertilizers and using some chemicals in the early 70s, it was rare back then.

“The Butz farm policy is one that involves risk. On the one hand, the high production can lead to big surpluses and big drops in farm prices. On the other hand, heavy exports can lead to domestic shortages—and rises in consumer food prices, as they, indeed, did in 1972. But if the two stay in balance, if the production is matched by just the right amount of foreign sales and there is enough left over for the domestic market, then farmers will get a good income, consumers won’t pay inflated prices and the nation gets some help on its balance of payments problem.”

– Why they Love Earl Butz, New York Times opinion piece, published June 13, 1976.

Like their neighbors, the Fuller family farm grew and prospered under Butz’s progressive, but short-sighted, vision. Gail remembers January 1980 — every piece of equipment on their farm was less than two years old. His dad was avoiding a large tax burden from their abundant sales by buying all new equipment.

It seemed like a smart financial move. Then the 80s farm financial crisis hit.

Sharply falling commodity prices, exacerbated by record crop production and the 1980s grain embargo against the Soviet Union combined with record high on-farm debt loads. Farmland values plummeted and farmers couldn’t pay off fortunes spent just the year previous on chemical fertilizers and new equipment. It was the worst agricultural crisis since the 1930’s Great Depression.

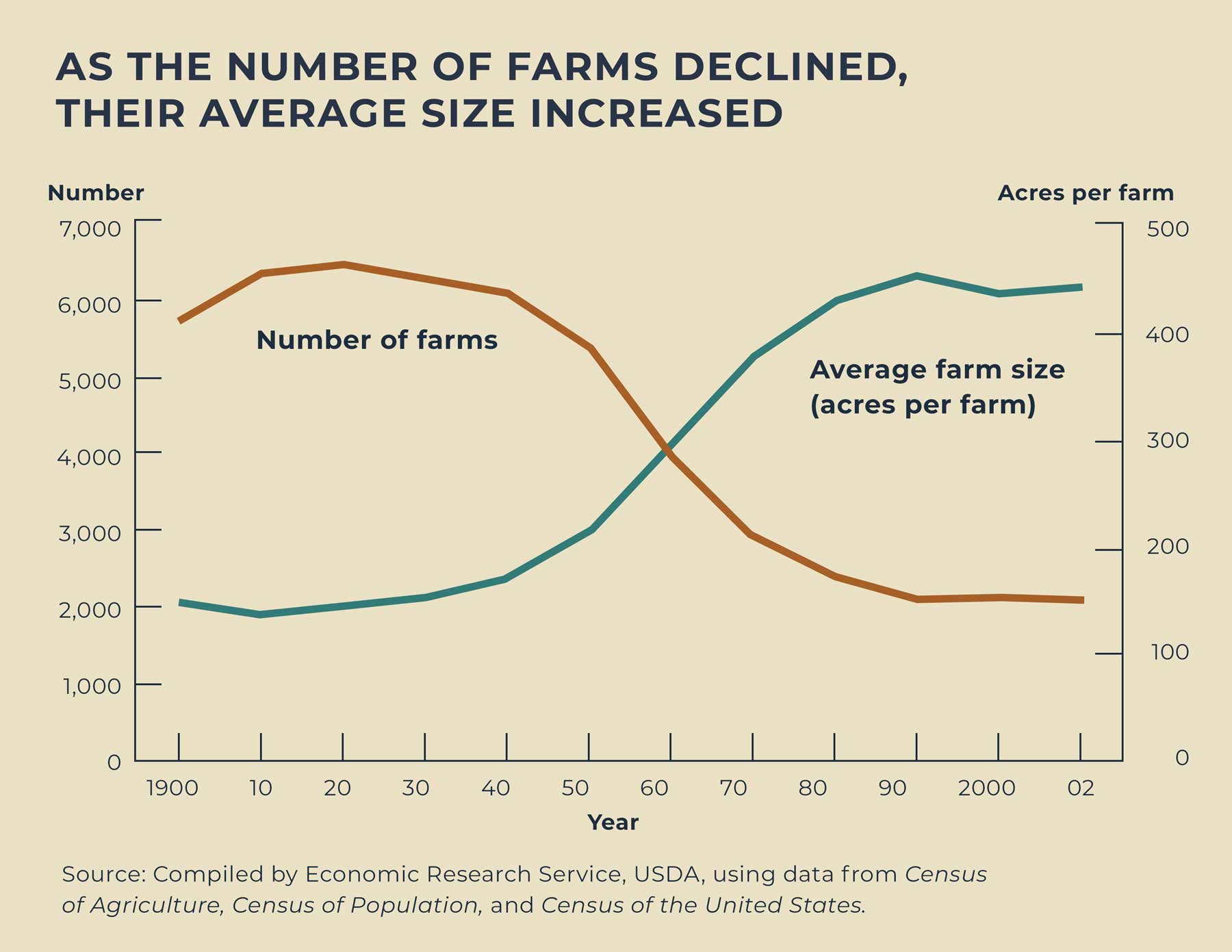

The number of farms in America shrunk dramatically through the 70s and 80s while the acreage of the farms remaining increased. The big farms gobbled up the small ones and cheap food production became, and remained, the name of the game.

Failing at No-Till and Winning at Regeneration

He wasn’t wrong. It’s just he wasn’t entirely right, either.

No-till practices prevent erosion by never leaving soils exposed. Cover crops are a crop such as hairy vetch or barley that is planted and killed, either through the use of chemical herbicides or specialized ‘roller/crimper’ equipment that crush the cover crop to the soil level. Or farmers plant their “cash crop” into the crop residue left over from the previous rotation without tilling the ground first.

It wasn’t the wheat per se, it was the carbon that was coming into my system with the wheat crop and the extra straw.

Yields went up, erosion went down and Fuller realized how much he didn’t know.

“I knew nothing about the soil other than to plant a seed into it,” he says. “I didn’t know soil is supposed to be alive. I didn’t know earthworms were good for anything other than fishing. I didn’t know there was a microbiome, none of that. And here I am farming 3200 acres. My neighbors were the same way.”

Once he started learning the foundation of soil health and regenerative practices, it was like “lighting a fuse,” Fuller recalls. Within five years he was planting 20 different crops in a five-year rotation. He was growing sorghum, barley and sunflower and was “starting to understand the power of diversity.”

Over a twenty-year period, he increased his farm’s soil organic matter from 2% to 7%.

(Organic matter is the carbon-based material — often called humus — which makes up healthy soils and supports the underground microbiome. Apropos, the ancient, pre-Latin origin of the word humus combined with the word homo, meaning man, homo sapien, was the derivative of the word “human.” It’s literal meaning is ‘being of the earth.’)

Fuller and his partner, Lynnette Miller, brought back animals into their crop rotation, adding cows, sheep, chickens, geese, ducks and pigs. The farm became extremely drought, flood and climate change resilient. His soil went from no worms per shovel scoop, to a few worms, to so many worms he couldn’t count them.

But despite those successes, Fuller still had a problem. Glyphosate.

The No-Till Chemical Trade-Off

A tradeoff for many no-till farmers has been increased herbicide use. Without tillage disturbing the soil and killing off weeds, no-till farmers depend heavily on other means to kill off weeds in their crops — namely glyphosate — and still harvest a yield abundant enough to at least attempt to cover their bills (including the expensive RoundUp Ready, GMO seeds). Although some no-till farmers are able to slowly wean themselves off herbicide use as their soil health increases, many, like Fuller, find themselves using even more.

While organic no-till practices are starting to gain traction, most no-till farmers (no-till cropland now accounts for 35% of cropland in the United States) use herbicides. Corn and soy no-till fields have doubled over the last decade and ninety percent of corn and soy cropland is planted with GMO, aka RoundUp Ready, seed.

“I was a heavy user of RoundUp, using more than my neighbors,” Fuller says. “So, I was also an early innovator in resistance weeds.”

Weed resistance is a major black-eye for the agrochemical industry, estimated to cost U.S. farmers as much as $2 billion a year. Glyphosate is the most commonly fingered herbicide with weed resistance issues, but other herbicides like 2,4-D and dicamba, have joined the club. In Kansas, 23 weed species are herbicide resistance (some to more than one type of herbicide).

About the same time that his fields were being taken over like “wildfire” by glyphosate-resistance weeds, Fuller started getting suspicious that glyphosate wasn’t as “safe” as he had always been assured. He spent an evening listening to videos by Don Huber, PhD., the professor emeritus of plant pathology at Purdue University. Huber shocked the Big Ag world with a 2011 letter urging the USDA to delay approving more RoundUp Ready crops and urging more research into the effects of glyphosate on plant, soil and human health. Huber says that glyphosate acts like an antibiotic on the soil, altering the biology of the microbiome, increasing plants’ vulnerability to disease and acting as a biocide on beneficial organisms in the soil.

It was all new information to Fuller. But one thing he understood very clearly. Dosing his land for years with an antibiotic hadn’t been good for his soil, his crops or human health.

“When I heard the word antibiotic, it was 10:30 at night. I almost threw up,” Fuller remembers.

Paraquat, first introduced in 1961, is a highly toxic, “knock-down” herbicide that works within hours of spraying. It is banned in 32 countries yet is legal in the U.S. for licensed commercial sprayers (aka farmers) to use. Paraquat is so deadly it is included in the list of toxic chemical agents — between mustard gas and ricin — by the Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Since then, Fuller has struggled with depression, exacerbated by, he suspects, his chemical exposure. A 2013 study of agricultural workers in France found an association between prolonged herbicide exposure and depression and pushed for increased research into the “possibility that environmental contaminants could affect psychological health” of farm workers.

Paraquat, although it hasn’t been directly linked to mental health illness, has been clearly shown to create other health problems for farmers. A 2011 U.S. National Institutes of Health study linked paraquat use and increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in farm workers.

“I wasn’t told about reentry times. I was running the planter and the sprayer… and was out there breathing that for three years.”

The same sector that was applauding his conservation practices — Fuller was awarded 2013 National Conservation Legacy Award from the National Soybean Association — was throwing him under the bus for the very same practices they were celebrating him for. Citing restrictions on the use of cover crops, the Federal Crop Insurance program denied his six-figure claim to cover devastating losses in yield.

After a several-year legal battle the USDA clarified the issue in Fuller’s favor and an arbitrator ruled to overturn the insurance denial. Fuller received his payment, a win for regenerative and no-till farmers. But the washout from the battle was rough. He lost his line of credit at the bank, his landlords cancelled farm leases because of his “risky” farm practices and in 2014 the USDA denied yet another insurance claim.

Despite all of Fuller’s proven successes in building soil health and diversity, the culmination of financial stress, the toxic toll of chemicals on his body and mental health and the peer pressure from a commodity ag community not on board with his regenerative vision became too much. It was time to start over.

They downsized, let go of the land and in 2019 Fuller and Lynnette relocated 50 miles south to a 162-acre farm.

“They say every farmer moves once in their life, right?” Fuller jokes. “This was ours.”

Through it All, Building a Regenerative Community

The “Fuller Field School welcomes rookies but this isn’t a workshop for beginners, Fuller warns. And it definitely isn’t about “free donuts” (a reference to the ubiquitous farmer workshop event). It’s a school. It’s in-depth, it’s tough and they’re going to learn something, he says.

Fuller speaks with reverence of past field schools and the greater experiences and relationship building the workshop fosters. Unlike most agricultural workshops, that are often focused toward specific segments of agriculture — big farmers or small farmers, organic farmers or conventional farmers — the field school is a “safe environment” for farmers of all sizes, types and levels of success (or failures) to come together, learn and share.

We’ve had 50 and 60-year-old white men break down and cry during the introduction, and you know, farmers don’t cry.

According to a 2020 study by the CDC, farmers are among the most likely to die by suicide, as compared to other occupations. Reporting by USA Today and the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting found that more than 450 farmers killed themselves across nine Midwestern states from 2014 to 2018. During the same time period, the crisis hotline operated by Farm Aid, a nonprofit agency whose mission is to help farmers keep their land, experienced a near doubling of calls.

“Once they show up they know they can open up and say things,” Fuller says.

And that’s part of why we’re going to take on depression this year, because we know we’ve built a safe environment for farmers.

“We have hardcore left and hardcore right (at the school). We have organic, conventional and permaculture (farmers). The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) and the NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) all show up, sit down at the same table and there’s no fist-fights,” Fuller says. The Fuller Field School is sacred ground.

“Gail brings reality. He brings it down to the farm level,” Gnad says. “He’s not afraid to tackle the hard topics whether it’s farmer mental health or farm bankruptcy. He’s gone through all that and brings a level of humbleness to the table.”

For Fuller, the regenerative agriculture movement is about a lot more than soil — it’s a paradigm shift in the way we grow food (and farmers) in America. Create a structure, build the community, generate the consumer support for farmers that invest in the change and the farmers will do so. Gladly.

Fuller envisions a future with more farmers on the land, not less. Thriving rural communities. Mom-and-pop stores. Families, schools and kids in them. A future where farmers aren’t selling “commodity crops” to just a few giant corporations, but real food, grown well, for their community.

Regenerating the New (Old) Farm

The new farmland is degraded, and the organic matter horrible. But he and Miller hope to rebuild the soil health quickly by applying their hard-lessons learned. There will be no chemicals sprayed on the new farm, that’s a prerogative.

The farm is a mix of native grass, organic cropland, timber, an orchard, a market garden and even a greenhouse. Fuller is excited to showcase all the types of regenerative agricultural production — livestock, vegetables, fruit, timber and grains — possible in Midwest farmlands.

There’s a lot more to be had than just corn and soy in Kansas.

They’ve brought over their small herd of 16 British White cows, a historic, dual-purpose (good for meat and milk) endangered UK breed. And Lynnette’s 75 Katahdin sheep, a famously rugged “hair” sheep breed that doesn’t produce wool but is great for meat and well suited to regeneratively-grazed farms. They have pigs, chickens (both layers and meat) and a small flock of Muscovy ducks. Their first batch of chicks comes in less than two weeks.

There’s a lot of work to do and it’s a race to regenerate the land before climate change makes the job even harder. Fuller finished seeding in early cover crops last week, right before the recent round of rain hit. That was a relief. Their first six months on the farm they were rained out of planting all but five days.

While we’re talking, Fuller takes a quick break to meet a scheduled truck delivery with 1500 pounds of regeneratively-grown seed potatoes from a regenerative potato farmer friend he knows in Colorado.

Within days there’s a post up on Fuller’s Circle 7 Farm Facebook page, inviting friends and customers to pick up potatoes. Yukon Gold, Gold Asterix, Rocky Mountain Russet, Yellow Finn, Kennebec and Purple Majesty. Sales are brisk, come get them while they are available!

Fuller’s regenerative farming tale is one made up of moments in time and lessons learned. Living the failure of a “cheap food” farm policy and experiencing it’s devastating effect on the rural farm communities of his childhood shaped the man he is today. Failing and succeeding beyond expectations at building soil health and regenerating tired farmland proved the promise. Struggling to eliminate toxic chemical farm addictions and battling with depression while taking on unfair governmental policies and refusing to bow to peer pressure showed him just how much work there is yet to be done.

Those were all the “snowflakes” that have shaped his life. But Fuller’s “blizzard” is really about community. Even when that’s something as simple, yet powerful, as sharing with friends and neighbors a pallet load of regeneratively-grown seed potatoes.

It’s good intentions and new beginnings, wrapped up in that simple act of faith that farmers take, every spring, when planting season begins and they sow this year’s new crop. Or, in this case, a pallet of regeneratively-grown seed potatoes, shared with friends.

Visual art, video and photography by Leia Marasovich.