MEET A FARMER

DEL FICKE

Ficke Cattle Company is located on the occupied homelands of the Pawnee and Jiwere people.

“Good soil smells beautiful. Depleted soil smells like dirt. There’s no smell. I’m probably as famous for sniffing soil as anyone on Earth. I’ve made everyone sniff soil that’s come to the farm. It’s a drug,” Del says.

Del’s serious. As far as he’s concerned, the soil is where it’s at. Del made it his mission to regenerate healthy soil via another life-long passion of his – cattle. But not just any cows, Del breeds cows purposefully chosen to thrive on grass pasture with as little human help as possible.

Which seems strange, doesn’t it? Cows evolved to eat grass. Yes they did, Del explains, but a grass diet wasn’t enough to raise the monster, steak-producing machines that the commercial cattle industry currently demands.

Not to mention, the processors and packers control the end market.

Just four meat-packers own 85% of the U.S. beef supply.

So, what does the type of cow you raise have to do with the soil? Well, everything. Because as Del and many other regenerative ranchers have discovered, well-managed grazing builds healthy soil and restores ecosystems that grow more grass to support more cows. But they can’t do it without the cows that are genetically predisposed to thrive in those conditions.

Though to hear Del tell it, he’s not learned any new amazing ranching and farming secrets. He’s simply carrying on a long Ficke family tradition and fulfilling the realization of lessons he learned as a young boy. Farmers work better when they work with nature, not against it.

Del and his wife Brenda have been the fifth generation to work the Ficke Cattle Company and the land that comes with it. The sixth-generation is his son Austin and his wife Alyssa, now in charge of the cattle business with Del’s guiding hand. His grandchildren, Attley, Hayden and Olivia, will be the seventh.

They currently are raising about 100 cows on just under 500 acres on land just south of where Del’s relatives settled on in 1869.

What we’re doing now,

it’s nothing new,

Following in His Grandfather’s Footsteps

Adolph was a barefooted, walking-stick-in-hand sort of fellow that even at 82 years old boasted a sculpted physique worthy of an aging Adonis. He spoke Latin and Greek, though he hadn’t gone beyond eighth grade in school.

His grandfather would point out and name native plants to his young grandson on their farm walks. Today Del does the same thing with his daughter-in-law Alyssa, albeit with the help of a cell phone camera and native plant identification app.

For the Ficke family, spotting new plant species confirms they are on the right path to regeneration. Through a process of trial and error, Del and Austin developed a system they call “Prairie Rehab,” taking tilled farm ground straight out of farm production and restoring it to productive, healthy grassland.

What hay the cows don’t eat, they stomp into the ground along with their manure and urine, a potent mix of minerals, nutrients and natural microbes that builds up organic matter. The soil rebounds quickly. Within a matter of three to five years, what was once tilled and struggling farmland has grown a lush pasture. Now it becomes part of their Ficke’s managed grazing rotation for the herd.

On a near-daily basis, Austin, Del and Alyssa take down and set back up portable, electric-charged fence-line to move the cows from pasture to pasture. The constant movement allows the cows to graze just enough so as to not damage the grass while encouraging a new spurt of growth and building organic matter in the soil to support that growth by leaving behind their manure and urine.

Within this mix of reclamation and regeneration, Del has seen local native species long gone pop back up to reclaim their ancestral home. Del figures they have 100 species now well established on what was once former cropland.

I’m a firm believer that every seed that God created is still in the soil someplace. We just have to get to a point to encourage it. Nothing is extinct.

What the Ficke’s learned by trial and error has been confirmed by science. In September 2020, a study published in Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems found that managed grazing techniques using cattle can indeed build carbon back into the soil, healing degraded ecosystems and restoring biodiversity in the process.

Adolph, as Del recalls, would watch for water trickling out of low spots across the farm. Once spotted, he’d dig out the natural spring to encourage a naturally-replenishing watering hole. It is a simple trick the Ficke’s use to this day. Especially important because water is a scarce commodity on the land.

Their best wells are dug 400 feet deep yet produce a measly 15 gallons a minute, so little that on a scorching Nebraska summer day, the farm’s 150-pound chocolate lab “can damn near drink the hydrant dry,” as Del puts it.

So, those Ficke-encouraged natural springs have been crucial to keeping the family’s cattle operation running. This past summer, they worked to enhance them, spreading hay bales across restored creek beds to naturally enhance the habitat, the same methodology they use for rebuilding pastures.

Though ironically, there were periods in the farm’s history those low-tech watering holes seemed like more trouble than they were worth. Del’s father, Kenneth Ficke, would cuss and complain that the springs prevented him from crossing the farm where he wanted without getting bogged down, expensive equipment in tow. Those complaints were the sign of those times.

Surviving the 1980s Farm Crisis

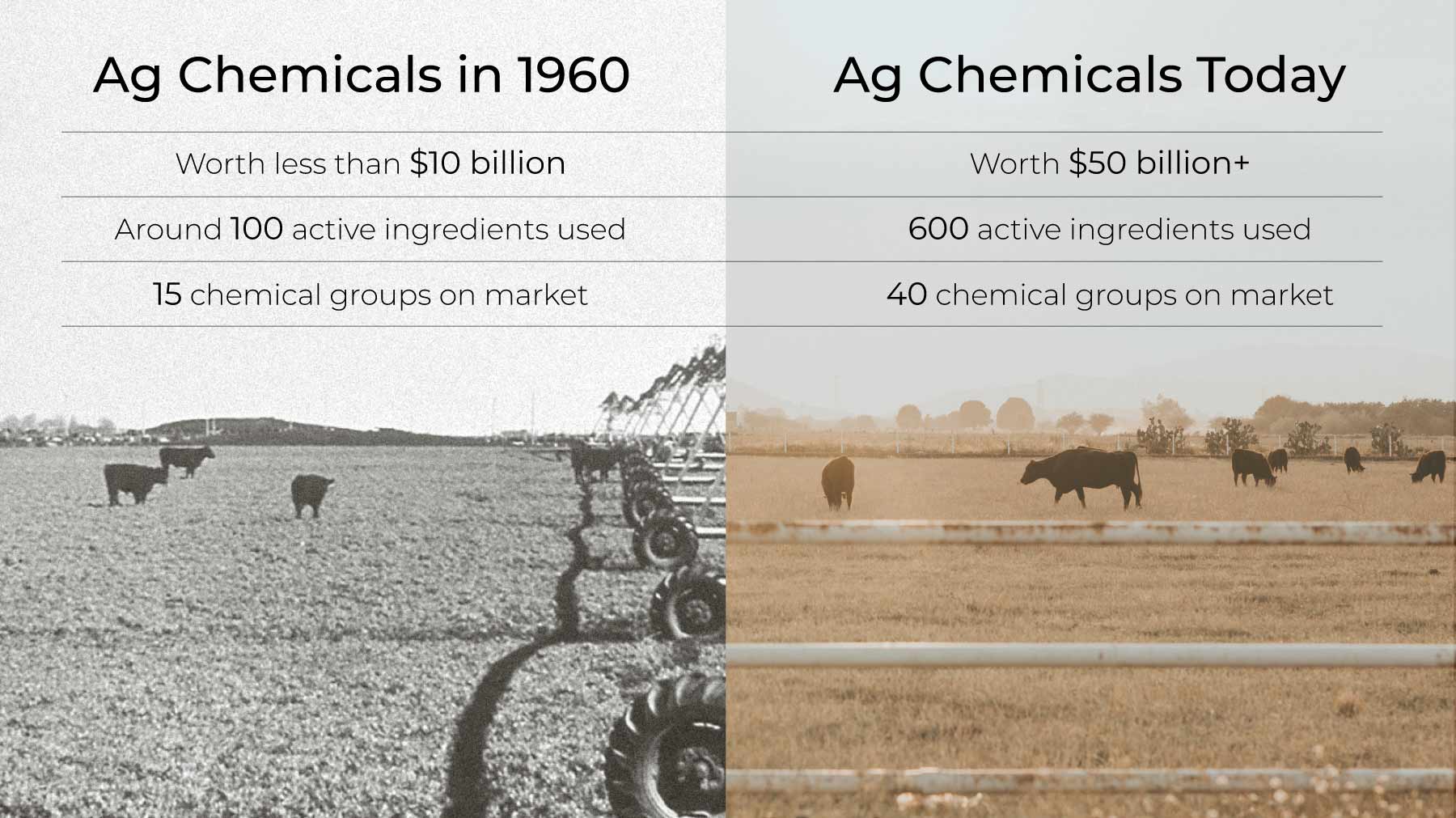

Overwhelmingly, farmers and ranchers of the mid-1900s, post-World War II era, left behind the practices of their fathers and grandfathers. They were lured by the promises of significant scientific innovations, chemical-based farming that would feed the world and line farmers’ pocketbooks.

But for many, including Kenneth, the bubble would quickly burst.

Del remembers his father as a perfectionist and an innovator. He believed in the latest advice and technology. But that came with consequences nobody was warning farmers about.

Go into debt buying expensive equipment. Purchase annual “inputs,” fertilizers and chemicals, aka “crop protection,” to prevent disease and stave off pests. Treat the cows with expensive pharmaceuticals. It was all part of the process they were told would make them better farmers and ranchers.

Instead of leaving the cows for the majority of the year out to pasture, a silo was erected. They started growing and chopping corn silage to feed the cows, finishing them off in a feedlot system before shipping them to auction. Pasture time was just a few months in the summer. That meant growing, chopping and feeding silage, plus dealing with the copious amount of manure the contained herd created by mechanically removing and spreading it on their farm fields in the summer.

It was a lot of work and Del hated it. But according to the experts, they were doing everything right.

These people certainly didn’t have nature or the farmer at the center of their heart,

The farm struggled to survive. They were running around 1000 acres and Del’s father, half-jokingly, referred to the farm as “Hell’s Half Acre,” an apt description. During the 1980s farm crisis, millions of American farms and ranches were lost to bank foreclosures, the victim of their increasing debt loads compounded by plummeting prices of agricultural commodities.

I still have PTSD over the 80s. We didn’t lose the farm. But we worked our asses off,

“I remember one fall, calves were selling for about $280 a piece and we were getting $1800 a piece out of our calves. We got lucky through that time that we had a different avenue,” Del says.

Before the 80s were even over, Del’s father was ready to turn over the responsibility of the farm. When Del was just 20, he took over. His father didn’t have a lot of debt on the farm when he passed it to Del, but Del’s mother is a straight shooter and as she told Del later, “I had a lot of things dumped on me.”

Del started making his own way — and mistakes. But it was a round of serious health problems that pointed him in the right direction.

The Path to Change

The first thing Del did after taking over was increase their acreage. He was still locked into the false promise that ‘bigger was better’ for farmers. Before too long, they had more cows than ever and Del was farming row crops as well.

But in 1999, his back went out and he required surgery. A doctor told Del, “if you get back into a tractor, you’re going to be paralyzed.” By then, he was farming 6,000 to 7,000 acres, growing corn, soybeans, sorghum, alfalfa, wheat, barley, grazing cover crops and even specialty crops. But he still wasn’t profitable.

In hindsight, his back problems saved him from even worse mistakes, he says.“We had a chance to rent a lot of different land from people. We were into the grain side on a larger scale than we could have ever imagined. Thank god my back blew up. We probably would have stayed with it,” Del recalls.

Del backed away from the farm and let a cousin take over. His dad has kept the cattle program alive, they were still operating their cow and calf and feedlot program. Del’s dreaded silage operation stayed up and running. To pay the bills, Del went to school and got into hospital administration.

But somewhere during all this upheaval, Del and his father had a heart-to-heart about the cows. They were both tired of writing checks. Feed bills, silage equipment, paying the veterinarian. But out of that desperation sparked inspiration. What if they bred a different kind of cow that didn’t suck their checkbook dry?

During those tumultuous 1980s years, Kenneth started cross-breeding their prize-winning Herefords to a “composite” bull. A composite cow is a hybridized cattle breed created using a large population of cattle types to create uniform animals with the same percentage of a specific mix of breeds. Instead of pedigreed animals bred for show rings and packing houses, the composite cows were vigorous and healthy with all the good traits of many cattle breeds without the bad.

Kenneth saw the promise but hadn’t yet taken the leap.

“My dad said to me…

So, they rolled their registered Herefords into the new breeding program, looking for that perfect “composite” cow. They launched the Ficke Cattle Company’s line of cattle genetics, Graze Master Genetics®.

The Graze Masters cows aren’t a commodity cow, bred for a feedlot. They are meant to thrive on grass and pasture conditions, Del says.

The new concept started to work. Del stopped growing silage and sold the equipment. They didn’t need it anymore. The farm’s soil was regenerating. They had enough pasture and the cows thrived.

Today, the Fickes raise about the same number of cattle as Del did in 1999 but with many fewer acres. They have increased the health of their grass pastures which means their “carrying capacity,” or how many cows they can support per acre, has grown by 60%. They’ve eliminated their need for chemical weed control by 95%. They’ve reduced their veterinarian bill by 90% and their hay bill by 60%. They don’t worm their cows; they use natural dewormers, including birdsfoot trefoil, a native plant.

While the Graze Master program was growing, Del was running a medical clinic in the city. He was surprised to hear the clinic’s patients complain about farmers and their practices. So he went home and talked to his dad about it.

So, the Ficke’s began selling their beef locally rather than through the auction yards. The Ficke Cattle Company quickly gained a loyal following of customers. Today Alyssa runs the direct market side of Ficke Cattle Company.

This meant Ficke Cattle Company was in an unique position compared to the majority of America’s ranchers — they were no longer at the mercy of the wholesale marketplace. They could find their customer base. And fellow ranchers were interested in the genetics and the grazing ranching practices the Ficke Cattle Company was finding success with. At the same time, the regenerative agriculture movement was gaining steam.

Spreading the Regenerative Message

But he did it. At first angry and still bitter over the struggles they had experienced, his frustration with the agricultural system and even his fellow farmers and ranchers.

“I was sick of seeing what we were doing to the environment. I was tired of seeing what the communities were doing and society and how it had changed from when I was a little boy. Enough was enough. I really came out guns blazing.” Del says. “I wanted people to know that this was serious. I didn’t cut anyone any slack. I didn’t give anybody any excuse not to be able to do what I was doing.”

But over time, his tone has softened. He is, after all, a rancher and farmer himself. Del understands the pressure and what farmers and ranchers face when they look at fundamentally changing their practices.

We’re in a very critical un-learning process right now. And that process can be very difficult,

Or, for that matter, even their sheep.

“Our phone rings constantly and there’s never anyone that we don’t talk to,” Del explains. “We have a consulting business, but I spent two hours on the phone last week with a lady that has 40 sheep. Well, that’s a person that’s never going to pay us big money to consult. But boy, what a great conversation. And what is she going to do now? Well, she’s going to do great things.”

Del’s simply teaching the same lessons he learned as a young boy from his grandfather.

We call it natural by tradition. It’s what we’ve always done. Isn’t it amazing? The more you step back and let nature take over, the better it is.