Bouquets

of Pesticides

The Real Journey of Flowers

Intersectional Community Strategist

The Victorian language of flower giving was once known as a way to convey romantic expression. But from a regenerative lens – the language of flowers seems to speak only of injustice.

How are these flowers grown?

Who is growing these flowers?

Where are America’s local flower growers?

Are our local growers growing regeneratively?

The U.S. requires imported flowers to be bug-free, but unlike edible fruits and vegetables they are not tested for chemical residues.

The most active substances that were tested reached concentrations that are approximately 1,000 times above the maximum limit set for food.

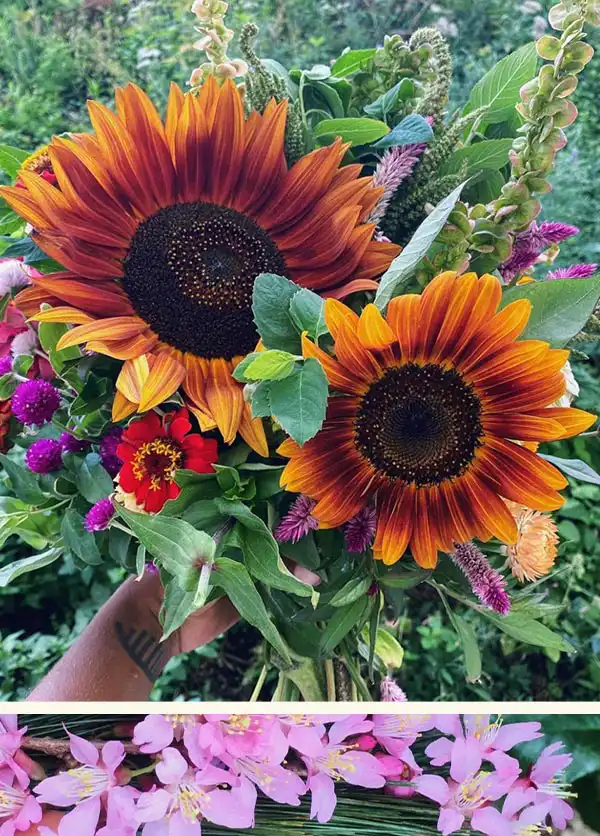

Here’s a look at regeneratively grown, seasonally arranged flowers :

What a privilege it is that these flowers are on the market and readily available to us.

This is part one of a two series blog on the true nature of the flower industry and race. The second piece will be released on Valentine’s Day.

If you’d like to purchase local flowers:

localflowers.org/find-flowers

Association of Specialty Cut Flower Growers

Flower Bucket Challenge

Slow Flowers

American Flowers Week

Slow Flowers Podcast

Certified American Grown

Field to Vase Dinners